"Nihil tam absurde dici potest quod non dicatur ab aliquo philosophorum."

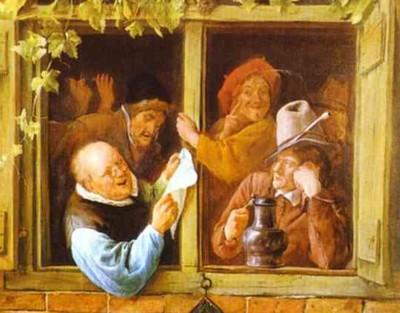

(Jan Steen. Rhetoricians at a Window. Source)

Let's Adore Jesus-Eucharist! | Home >> Philosophy

"Nihil tam absurde dici potest quod non dicatur ab aliquo philosophorum."

(Jan Steen. Rhetoricians at a Window.

Source)

We often hear people claiming that Philosophy is not a science, or at least not a serious science, because all philosophers contradict each other.

Do philosophers actually contradict each other? Let's try to examine this assertion a bit more closely:

2.1) Who is, and who isn't a philosopher? Suppose you wanted to pass judgment on all physicians, but you defined a "physician" as anybody who claimed they could heal somebody of a physical ailment. In that case, you would consider quack doctors, witch doctors, faith healers, and medicine men to be in the same category as real physicians who graduated from recognized medical schools! Don't you think there would be quite a few disagreements within of your "set of physicians"? What about philosophers? Is it reasonable to define a "philosopher" as anybody with an opinion and a soapbox on which to stand?

2.2) Who are all the philosophers? My favorite book on the History of Philosophy (which is actually only an overview, and not a full treatment of the subject) lists about 700 philosophers (and those are only the famous ones). Can you name them all off the top of your head? No? Then how can you talk about "all" the philosophers?

2.3) What are all of the assertions for each philosopher? I don't know any "Single-Assertion philosophers". Most assert many (too many?) things. To compare only two philosophers, you would need to compare each assertion of one philosopher to each other assertion by the other philosopher. My math has always been shaky, but that smells of a "Cartesian Product". If we can't list all of the assertions of even a single philosopher, never mind the full comparison between two philosophers, how can we claim something about all of the assertions of all philosophers?

2.4) What is a contradiction? My teachers have led me to believe that there are many "flavors" of opposition between two assertions:

2.4.1) Contrary. Example: "All Arabs are terrorists" and "No Arabs are terrorists". Both can be false at the same time, but both cannot be true at the same time.

2.4.2) Sub-Contrary. Example: "Some dogs are black" and "Some dogs are not black". Both can be true at the same time, but both cannot be false at the same time.

2.4.3) Contradictory. Example: "All vehicles pollute" and "Some vehicles don't pollute". One is false, and the other one is true; they can't both be false or both be true at the same time. They contradict each other.

Have you classified each relation between each set of two assertions, according to their "flavor" of opposition? How then could you say philosophers "contradict" each other?

2.5) What level of certainty does this philosopher give to his assertion? We've all blurted out some pretty silly stuff at some point or other of our lives. Ideally, all philosophers would either refrain from talking, or say things which they had thoroughly researched. Knowing what we know about human nature, that is a rather faint possibility. Are you sure this philosopher wouldn't recant this assertion, if somebody reasonably objected to it? In other words, did this philosopher himself claim a high level of certainty for his assertion? Or was he just offering a probable opinion? Or even, was he having a bad day?

2.6) What exactly does this philosopher mean with this assertion? Before you even compare one assertion of one philosopher with anything else, are you sure you've really understood what that philosopher meant? I've seen many philosophers who had their own special terminology, which was sometimes just ordinary words given new meanings. Are you really sure you understand what each philosopher was trying to say?

2.7) Why did this philosopher claim this assertion? I once had a Math teacher who corrected her exams in an amazing way: she would start by grading your answer to each problem, but then, if your answer was wrong, she would re-do your whole calculation step-by-step. If you had made a little mistake somewhere, she would remove points for that mistake, but then continue the calculations assuming your mistaken step was in fact correct! If the rest of your calculations were right, she would only remove points for that small mistake! I have seen a few philosophers who have made the effort to "follow the calculations" of other philosophers, and then show that actually both agreed far more than was apparent, because once a little mistake here or there was corrected, their positions converged. Have you made that effort?

2.8) Do philosophers disagree more with each other than plumbers? Yes, I'm quite willing to grant that plumbers disagree a lot less than philosophers. But are these two types of activities of equal difficulty? Another way of saying this is that Philosophy "resolves" to the intellect, whereas plumbing "resolves" to the senses. If you don't connect a pipe properly, something will come out. You'll see it, feel it, maybe even smell it! But if you make a mistake in a philosophical inference, only an intelligent and astute person will notice it. If your mistake happens to be phrased in an exquisitely crafted sentence, with many appealing metaphors, then probably most untrained thinkers will miss it.

2.9) Does your professional activity have the potential of accusing your personal life? The last part of Philosophy is Ethics (or "Morality", it's the same thing). Ethics is based on the three preceding parts of Philosophy (Logic, Physics or Philosophy of Nature, and Metaphysics). Ethics sooner or later deals with delicate questions like divorce, theft, drugs, lies, adultery, abortion, etc. A Math teacher who is a corrupt, dishonest person can still explain partial differential equations quite well. But a philosopher cannot dissociate his philosophical theories from his personal life quite so easily. Have you examined the personal life of each philosopher, to see if it might influence his thought? (See also "None More Blind Than He Who Doesn't Want To See".)

Do all philosophers contradict each other? Strictly speaking, no. For example, Aristotle and Saint Thomas Aquinas agree on many, many topics. Thomistic philosophers in general agree quite a bit with each other.

There is a "Philosophia Perennis", an Eternal Philosophy. If you can't see it, you have a problem. It's like losing weight. If you get up one day and you decide that from now on, you want to see your toes, you'll go on the best and only diet there ever will be: "Eat Less, Eat Better, and Move More!" But if you get up one day and decide you want to see the "Philosophia Perennis", you'll have to go on a "Philosophical Diet":

Assert Less, Assert Better, and Question More!

Let's Adore Jesus-Eucharist! | Home >> Philosophy