MEC (Mountain Equipment Coop).

Let's Adore Jesus-Eucharist! | Home >> Varia >> Bachelor's Kit

MEC (Mountain Equipment Coop).

1) Introduction

2) What is the "Boudoir Effect"?

3) Could the MEC plant a piton into the slippery slope of

fashion?

4) General characteristics of "VeloHobo"

5) VeloHobo pockets

6) VeloHobo zippers

7) Why I don't like Gore-Tex

8) A separate waterproof layer?

9) Some specific articles of VeloHobo clothing

10) VeloHobo packs

11) VeloHobo bicycle

12) Other VeloHobo articles

13) Conclusion

14) Post-Scriptum

Appendix 1) Previous research on natural convection cooling

Appendix 2) How could the waterproof layer be separated from

the body?

I love the MEC (Mountain Equipment Coop). I've been shopping at the MEC for over twenty years, and I hope they will bury me with my MEC Membership Card stuck in my cold, dead hands. (Note for non-Canadians: the MEC is a well-liked store here in Canada, that traditionally has supplied excellent clothing and gear for mountain climbing, hiking, camping, etc., and all this for reasonable prices.)

That being said, I seem to have noticed a sad negative trend in the quality and design of MEC clothing and gear. These days, I'm starting to wonder whether "MEC" will soon stand for "Boudoir Equipment Coop". (Note: A "boudoir" is a French word for a dainty little room where rich ladies can gossip and fix their makup.)

Is this just an impression that has no connection with reality? I hope so! I'm told the Quebec City store doesn't carry much stock, and I've never done a scientific study, comparing MEC clothing and gear over a period of decades. But if I look at all the clothing I wear and gear I use, the "MEC Percentage" seems to be steadily going down. Could this be caused by the dreaded "Boudoir Effect"?

This man is not dressed for success in a boudoir!

The MEC tries to supply clothing and equipment that is high-quality and reasonably-priced, designed for self-propelled outdoor activities, and manufactured in a socially-responsible way.

This is a high standard, and like all high standards, it's hard to attain, and even when attained, it's hard to keep. Like a society struggling against religious obscurantism, or a Christian struggling against sin, the MEC can never say: "We've won! We never have to worry about this again!" The Boudoir Effect is an ever-present threat.

Why? Because selling rags will always pay very well, and be very easy to do. Just take a walk in a shopping mall to see. The MEC can multiply its profits just by selling fashionable rags instead of real outdoor clothing and gear. Not only is it vastly more profitable, but because of the democratic aspect of MEC management, it could very well one day be more pleasing to the majority of customers! (Remember that as MEC membership goes up, the proportion of knowledgeable and hard-core enthusiasts will go down, unless measures are taken to oppose this natural trend.)

Let's try to list some characteristics of the Boudoir Effect:

2.1) Fashion churn instead of timeless designs. You can never buy the same thing twice. To raise profits and maintain customer interest, the products constantly change. For example, I can't seem to buy the same shoes or boots at the MEC, within a one-year interval. Same for rain gear, at a longer interval.

2.2) Short lifespan instead of durability. For example, pedals purchased at the MEC that omit O-rings worth twenty cents, and that will therefore be ruined in one season. The same pedals, because of the position of the locknuts, make it intensely difficult to clean and grease the bearings.

2.3) Showroom instead of mountain ridge performance. A product can unfortunately be designed to perform superbly in a well-lit, confortable showroom (instead of on a dark and wet mountain ridge). A "good product" becomes one that can captivate an audience and force their credit cards out of their wallets.

2.4) Form instead of function. For example, clothes have to "drape well" more than they have to last long or protect against the cold and rain. In a way, the phenomenal success of the Dilbert comic strip (some call it a documentary) is based on the natural antagonism between the marketing and engineering departments.

2.5) Visible gadgets instead of invisible ruggedness. You can see this phenomenon in some cars. To please customers, "gadgets" are added, like electrically-heated seats, a coffee mug holder, a great sound system, etc. This sells more than just saying: "Instead of adding unnecessary gadgets, we've tightened up machining tolerances in the transmission, so it will last an extra 20000 Km."

2.6) Many specialized pockets instead of few large general pockets. Instead of a few seriously large and unspecialized pockets, clothing and gear infected with the Boudoir Effect will have many little pockets, one for your lipstick, one for your face powder, one for your cell phone, etc. (Honest, my latest pair of shorts from the MEC was almost as bad as that. I was so disappointed that I no longer buy shorts or pants from the MEC.)

2.7) One-man show instead of a team effort. A good piece of clothing or gear is designed to function as only one member of a team. A bad piece of equipment is like a hockey player who hogs the puck instead of letting other teammates score. In the same way, a product that tries to perform well in the showroom will tend to aggregate functions that should be left to other pieces of equipment or clothing. For example, rain pants that have pockets, instead of just slits to permit access to the pockets of the pants worn underneath.

Etc., etc...

When a climber wants to avoid falling, she finds a way of attaching herself. Couldn't the MEC somehow "plant a piton", to avoid being pulled down by the Boudoir Effect? Even if the MEC was currently absolutely pure of any contamination by the Boudoir Effect, wouldn't it be good idea to protect ourselves from this ever-present threat?

If so, what would this "piton" look like? My suggestion is the "VeloHobo" outdoor urban clothing and transportation system. I wish I could present a well-researched proposal, complete with technical drawings, but all I can muster is a few written thoughts and some amateur pictures. You will have to compensate with your imagination, technical competence, and indulgence.

I will first try to give some general characteristics of the "VeloHobo" system, then I'll try to give some specific details about each component.

A rough description of "VeloHobo" is a bag with all the clothing and gear you need to live outside all year long, and a bicycle and trailer to do that anywhere in any Canadian city. Here are a few general characteristics:

4.1) Timeless design. After an initial Research and Development effort, the "VeloHobo" design would be "frozen". A few minor improvements might be tolerated, let's say every three or five years, but normally it wouldn't change. This "frozen" design would be important, not only to avoid fashion churn, but also to be a benchmark against which the rest of MEC clothing and gear could be compared. So, for example, if ten years down the road the "VeloHobo" raincoat weighed and cost half as much as a more fashionable alternative on sale at the MEC, customers could start asking questions about the "Boudoir Effect"!

4.2) Integrated into the MEC's Constitution. To protect the MEC against an eventual "Boudoir Effect", it might be a good idea to integrate the "VeloHobo" (or something similar) into its Constitution. The MEC would have to offer such a product in all its stores, forever. I claim this would become more important as the MEC customer base enlarges, which means more and more customers who are less technically knowledgeable, and less enclined to engage in hard-core outdoor activities.

4.3) Field testing team: Canadian hobos. The MEC gives money to help save little birds, and sells organic bicycle chain oil to reduce pollution, etc. Wouldn't it be nice if the MEC also made efforts to help protect Canadian men? Don't we have plenty of homeless persons who basically live outdoors 24 hours a day, 365 days a year? Maybe the MEC could make long-term clothing and gear loans to selected homeless persons, with the understanding that a MEC technician would drop by at regular intervals to study how the equipment is holding up? Not only would this be good corporate citizenship, but the equipment would probably be abused like no other testing team would abuse it, which is excellent for a Research and Development effort! (But of course, the testing team would include more than homeless persons, and environments other than urban.)

4.4) "Half-Dozen Twelves" Bicycle Design contest for Canadian universities. I don't know if it's just me, but it seems there are plenty of design contests for Canadian engineering students which involve building some sort of stupid gas-powered race vehicle. I've never heard of a design contest for something I really need (and planet Earth too; think about global warming): a commuter/mountain bike under 1200$ and under 12 kilograms, that I can ride for over 1200 kilometers a year, 12 months a year, for 12 years, with less than 12 minutes of maintenance a year. I'm not an engineer, but after having overhauled my own bike, and seen how poorly engineered many bicycle parts are, I think it could be done. I think the MEC should sponsor such a contest. Maybe it could be called the "Half-Dozen Twelves Contest"! The MEC could then come up with a "VeloHobo" seal of approval, so bicycle manufacturers would be encouraged to build such a beauty.

(For non-Canadians reading this article, you need to understand what "12 months a year" means. See Satan's Winter Sludge.)

4.5) Part of Canada's efforts to reduce global climate change. I continue to be amazed at how poorly Canadians can dress for winter, and how misadapted current bicycle designs are for our climate. If the MEC could come up with the "VeloHobo" system, more people would walk or ride their bicycles, which would decrease greenhouse gas emissions.

4.6) Effective, durable, simple, and not too expensive. Engineering is making compromises, so all aspects of a system cannot be maximized. For example, you can rarely have the least-expensive system, with the most features, designed in the least amount of time! So the priorities would be, in decreasing order: effective, durable, simple, and not too expensive. Aesthetics would be explicitely NOT part of the specifications. Also, even though simplicity is not the top priority, it would probably be the primary means to improve the designs, especially for clothing. Remember that one of the first victims of the Boudoir Effect is simplicity.

4.7) Just one of the MEC product lines. There is nothing wrong with the MEC satisfying other outdoor enthusiasts. "VeloHobo" is not meant to please ice climbers, or kayakists, etc. Because "VeloHobo" doesn't have to please everybody, it can afford to make some apparently rigid design decisions.

4.8) A name that helps break mental barriers. Many obstacles to technological improvements are actually cultural. When people aren't used to seeing something, they assume it must be bad. By calling our system "VeloHobo" (or something related to homeless persons), we reduce such inhibitions. Hobos are expected to look a bit weird, and to find clever low-cost solutions to outdoor clothing and gear problems. Another advantage of a catchy name is that the "Boudoir Effect" is not a technical problem, but a sociological problem. It all boils down to following trends set by other people, or making an effort to educate MEC members, so as to set our own trend.

Etc., etc...

Pockets are almost always too numerous, and too small. The First Law Of Pockets states that:

1 liter + 1 liter < 2 liters

In other words, 2 one-liter pockets contain less that one 2-liter pocket. It's better to have fewer and larger pockets, and when you need smaller compartments, you get a smaller, compartimentalized container which you just stick in the large pocket. (By the way, this rule also applies to toolboxes, packsacks, etc.) Unfortunately, the MEC these days seems to favor more and smaller pockets, which doesn't make sense. For example, this is what I carry with me on a very cold winter walk in Quebec City:

Mittens, tuque, balaclava, face mask, goggles

How am I supposed to fit that into the kind of pockets found on MEC coats these days? (The jacket used in this picture doesn't come from the MEC, but the pocket size is pretty representative.) My last MEC Gore-Tex jacket had 6 pockets, none of them big enough to contain even one single MEC mitten!

My right hand doesn't even fit into that pocket!

This is the kind of pocket I'd like to see on my outerwear:

Serious coat pocket

There would only be two pockets on the whole outerwear, both very large (no pockets on the pants, just slits to access the pant pockets). They would be zippered. Being inside the coat, they would be automatically waterproof, while being lighter since they could be made out of the wonderful little netting used by the MEC for the pockets of fleece jackets:

Wonderfully light and practical pocket netting

Pants and shorts are also a problem. Why can't MEC have decent cargo pockets like this?

Real pant pockets

I'm not saying MEC members should all start carrying 2 liter milk cartons in their pockets, but you'd be amazed just how handy those pockets can be. (For example, carrying a few hand tools over to your Mom's appartment to fix something, or carrying back a few items from the grocery store, etc.)

Another consideration about pockets is that they should be "centralized". I will always remember one cold night in the army when I had to find some small and important object on myself. I think I counted over 18 pockets. With four pockets on the pants (or shorts), and two large ones on the coat, you don't need more. The advantage of keeping the pockets on the pants is that you almost never part with your pants (as opposed to your coat, or fleece jacket, etc.), so you always know where your things are. Also, by reducing pocket count, the price of clothing drops.

Zippers are a wonderful invention, but the Boudoir Effect tends to multiply them unnecessarily. Zippers, because of their inherent complexity, will always be more fragile and less durable, on top of being less weatherproof.

A sad example of zipper overuse is for daypacks. I'm not talking here about the kind of little backpack used by school children, I'm talking about a serious daypack. Structural zippers, i.e. zippers used in locations where the main carrying pocket will be destroyed if a zipper fails, have no place on a serious daypack.

I've only owned two daypacks in my life: two MEC Klettersacks. The first one died after over fifteen years of daily service, and the other one looks ready for another fifteen years at least. Notice such a design doesn't put a zipper in a structural location. It's just one big pocket:

Simple and effective daypack

(I asked a salesman at the MEC a few weeks ago, and he couldn't find a comparable pack, and had never heard of "Klettersack". It doesn't show up on the MEC web site either, but I might be spelling it wrong.)

Another poor location for zippers is on rain pant legs. The water inevitably enters where the knee bends. (Not while walking normally, but while cycling.)

I've owned three MEC Gore-Tex rain garments (pants and jacket). All of them top-of-the-line, all of them "Guaranteed To Keep You Dry", etc. I'm starting to think that Gore-Tex, and in general any integrated waterproof or breathable layer, might not be the best solution for "VeloHobo" clothing. Here are some reasons why:

7.1) Not breathable enough. The sad fact is that when it really rains, I can't cycle to work without getting wet from prespiration. Gore-Tex just doesn't work (any fabric coated with rain will not let water vapor out).

7.2) Difficult to inspect. You're about to leave on an important trip. Is that Gore-Tex garment still waterproof? How could you tell without taking a shower with it?

7.3) High cost. These days, it seems like you need to put a second mortgage on the house to buy a Gore-Tex outfit!

7.4) Fragility. My first Gore-Tex outfit started leaking at the shoulders (where the backpack straps rub) long before the actual coat was worn out. My Gore-Tex boots also started leaking long before the actual boots were worn out.

7.5) Difficult to repair. I'm sure there is such a thing as a shop that can fix Gore-Tex garments, but I've never seen one. One of my sources claims the machine to tape the seams is worth 10 000$ CAN.

7.6) Fewer choices for thicknesses. Sometimes you need a very light but more fragile garment, sometimes you need something more robust even if it weighs more. Coated fabrics, especially Gore-Tex, give you far fewer weight choices than uncoated ones.

What if we tried to generalize the trick used for backpacks? A simple plastic liner is 100% waterproof, easy to inspect for leaks, dirt cheap, as robust as you are willing to carry (plastic comes in all kinds of thicknesses), and patchable with just about any kind of tape.

If it's airtight, it's watertight!

What about breathability? I've never tried this, but I think it might work: simple convection ventilation. Take an umbrella for example: if the water comes straight down (i.e. there is no wind), you will be guaranteed to stay dry, and you will have perfect ventilation. You might sweat if it's hot and humid outside, but you will not sweat because your raingear is restricting ventilation. The basic concept is just that: an umbrella, but that is windproof.

How can we get both the advantages of the perfect ventilation and perfect rainproofness of an umbrella, without having an umbrella? I wish I knew! My current best guess is:

- find a way to "push" the waterproof layer away from the skin, at least enough to allow a minimum of liters per minute of air to flow, so that air can pick up the heat and humidity from your body and throw it outside the clothing system, while also bringing in colder air to cool you down;

- only allow openings in the clothing system that "point downward" (think of a glass: if it "points up", you can fill it with water, if it "points down", you cannot put a single drop inside it, even if you put it under the open tap of your kitchen sink);

- use "one-way valves" and normal body motion to pump air (just like veins in the lower parts of our legs have one-way valves, and when our leg muscles contract and relax, that "pumps" our veins, which then tends to "jack up" the blood back up to our heart). More exertion should naturally increase ventilation under our raingear;

- use the "chimney effect": air between the waterproof layer and the body is heated, and rises naturally (hot air is less dense, so it will tend to rise), so for example, with a bit of cleverness, you can get hotter air rising out of the hood opening, and thereby drawing in cooler air from the ankle cuffs;

Of course, a real prototype would not look like this. The "foam spaghetti" (or whatever contraption used to push the waterproof layer away from the body), and the waterproof layer would not even be visible, but it gives you an idea of the concept:

Fully waterproof layer over "chimney effect" ventilation aid.

How large would this "chimney" need to be to match or surpass the "breathability" of Gore-Tex? I don't know. But see Appendix 1: Previous research on natural convection cooling for some ideas. How would this "chimney" or air passages be maintained? I don't know, but see Appendix 2 here below for some ideas.

This technique might have many advantages:

8.1) Possibly better ventilation than Gore-Tex, while being 100% waterproof. I might finally be able to cycle to work in a downpoor without getting either wet from the rain, or wet from prespiration!

8.2) Easy to fix, easy to replace waterproof layer. You could roll up the waterproof layer and carry it in a pocket of the outer layer. A full spare waterproof layer could probably be also carried for longer trips (it would not add much bulk or weight).

8.3) Low cost. I think I could hack together a prototype for a least half the price of a typical Gore-Tex outfit, and maybe even much less.

8.4) "Bombproof" outer layer. It's telling that the outer layer used in these conceptual pictures was purchased at the MEC a very long time ago for a low price, has been extensively used (including as work clothing), and has outlasted my Gore-Tex outfits! It's just one layer of nylon, no coating of any kind. Light. Bombproof. Fixable by anybody with a sewing machine. Would you dare crawl around basements to do plumbing while wearing your 500$ Gore-Tex outfit? Neither would I, but the cheapo nylon "powder suit" you see on that picture has crawled around in many basements. This obviously also applies to military uses. Can soldiers afford to molly-coddle their equipment in combat? (By the way, I also asked a MEC salesman if they had anything like that suit available today, and he said no.)

8.5) Easy thermal management. Since the outer layer would have drawstrings at all openings (leg bottoms, hips, cuffs, neck, etc.), you could completely cut off ventilation in colder weather.

8.6) Less shuffling of accessories for extremities. This sounds like a minor advantage, but I'm starting to think it would be quite nice. In the wintertime, you need all kinds of "accessories for extremities". Not only must you be able to store them, but you must not lose them either. I find myself shuffling my mitts, tuque, balaclava, mask, thin gloves, etc., between my big down parka (when it's really cold), my Gore-Tex outfit (if icing rain threatens), and my nylon powder suit (all other cases). If there is only one outer layer, you never need to do this. Plus you can have little "lanyards" at the wrists and neck to attach these accessories, so you never lose anything.

Etc.?

This technique would probably also have disadvantages:

8.10) Two of anything is fussier than just one. It will always be easier to manage a single-layer piece of clothing.

8.11) Bulky ventilation aids. Maybe the required size of ventilation aids will make you look like Mr. Michelin! And even if they are made of easily compressible foam, they couldn't be that compressible, otherwise they wouldn't be able to "push away" the waterproof layer. So the raincoat might end up being fairly large even when packed tightly. A good design would obviously have to minimize the size and number of these ventilation aids.

8.12) Greater susceptibility to tearing of the waterproof layer. By definition, if you separate the robust outer layer from the thin inner waterproof layer, the thin layer won't resist tearing as much. You can always increase the thickness of the waterproof layer, but then you end up with two heavy layers, instead of just one like Gore-Tex!

Etc.?

Some MEC clothing articles are nearly perfect as is. (The excellent Serratus fleece mittens and Gore-Tex overmitts come to mind.) So I will only list the articles which I think could be improved.

9.1) Shorts and pants. For years I constantly wore MEC shorts and pants. Then they started getting sillier and sillier. I've now switched to Surplus St-Gilles (Latulippe) Panarm pants, civilian colors, 65% polyester/35% cotton (www.army-surplus.ca). From what I can see, they are made in Canada (MEC is supposed to encourage Canadian manufacturers!). With the kind of purchasing power the MEC has, I'm pretty sure that company could manufacture a better version just for the MEC. Some suggestions: delete the flaps on the two top pockets (useless), delete the rear pocket (useless), delete the drawcord at the bottom of the pants (useless), make it available also as knee-length Bermuda shorts (I had to cut my pants to make shorts). I would also make the two top pockets out of that nice "pocket mesh netting". I'm pretty sure some cooling would occur, with the hot air rising up through the two front pockets. Also, I'd add some kind of slippery nylon patch inside the crotch, to reduce wear. This might just be me, but I always seem to wear out my pants in the same way: I eventually can see right through the bottom! Putting some sort of abrasion-resistant patch would probably double or triple the lifespan of such pants (at least for me).

9.2) Rain coat and pants.

(Notice that for me, "rain wear" means "all-year long wear", since I just

add layers of fleece for the winter.) For the sake of the argument, let's

suppose the idea outlined in

Section 8

here above doesn't work. My second-best choice would then be two sets: one

Gore-Tex rain coat and pant, and one "cheapo" uncoated nylon windbreaker coat

and pant. The "cheapo" set, being inexpensive and tough, is always the first

recourse. The Gore-Tex comes out of the pack only when it rains or get very

cold (that way the expensive and fragile Gore-Tex outfit lasts longer).

Both sets would be made with the same pattern, just the fabric would change.

The Gore-Tex would be three-ply (two-ply with lining blocks air flow

inside, so it causes more prespiration).

Coat: no pit zips, only two massive internal pockets, elasticized waist

drawcord, a cut that goes down well below the buttocks, nifty MEC hood that

can fit over a cycling helmet, etc. I would even consider a prototype that

would have enough space in the back to wear your daypack underneath

your rain coat. Not only would that reduce wear to the shoulder area of your

rain coat, and automatically keep your day pack dry, but it might actually

improve ventilation. When I cycle in the summer, I stuff something underneath

the pack, where the waist belt is, so there is a large air gap between my pack

and my back. If I could put my rain coat over this setup, I could get

much better ventilation. (See also

Section 8

here above. Anything that keeps the waterproof layer away from the body is

worth investigating.)

Pants: no pockets (just slits to reach the pants underneath), no zippers,

two Fastex buckles on each side above the pocket slits, to hold up the

pants.

9.3) Neoprene face mask.

Neoprene face mask

My life changed the day I got my first neoprene face mask. It is one of the smallest and cheapest pieces of clothing, yet it transforms Quebec winters from "horrible" to "cute" (but tends to have the opposite effect on your face!). Why don't we see them more often? Part of the reason is of course that they make you look "bad" in a boudoir (remember to pull it down before walking into a store!). A more serious reason is that good ones are very hard to find! I threw away the one I purchased from the MEC about a year ago. It is nearly useless. First, a bunch of silly little holes distributed in front of your face either makes it difficult to breath when you're jogging or pedaling hard (if there are not enough silly little holes), or lets the wind come right through and freeze your whole face (if there are enough silly little holes). You want just one big hole, directly in front of the mouth. (To get an idea of the size and shape of that hole, hold your index, annular and middle finger together in a slightly triangular shape, and stick them in your mouth; that's about the size of hole you want. Don't look at my current face mask: I kludged a bigger hole in it, while avoiding the main seam.) Second, the recent MEC version has silly fleece-like material on the inside. This guarantees a leaky joint between your mouth and the mask, so all the condensation accumulates over your entire face... So you freeze... And then when you get back inside, the mask doesn't dry because all this fleecy material absorbs water! Honest, a face mask for winter needs one single hole for the mouth, and it has to be as non-absorbent as possible. (Also, the neck strap needs far more velcro to stay put.)

9.4) Boots with integral gaiter. I've owned just about every kind of gaiter sold by the MEC over the years, and they have ALL proven unsatisfactory. Here are some reasons why:

9.4.1) Attachment under the foot arch. Always a part that wears out quickly (because it's subject to the same wear as the boot sole), always dirty and wet, etc. If the under-arch buckle is permanent and strong, those disadvantages are reduced, but not eliminated. If the under-arch attachment is just a string that must be fastened each time, it is a pain! (And of course, when the knot gets jammed with ice, it gets worse.)

9.4.2) Joint between the boot and the gaiter. If you walk long enough in hard and deep snow, some snow will come in between the gaiter and the boot, nullifying the very reason why you were wearing gaiters...

9.4.3) The fuss of yet another little piece of clothing. Something else to keep track of, something else to lose...

Pant-gaiters would eliminate #9.4.2, but not the rest, and they would complicate washing of the pants.

Why not just add a little fabric "sleeve" at the top of the boot? In other words, integrated "boot-gaiters"? Very little fabric would be necessary, just enough to provide a good seal on the bottom of the calf, just above the top of the boot. It would look unusual (hiking boots are now almost visual works of art), so fashion-conscious hikers would not like them, but to those of us who need to plow through heavy snowbanks on the way to school or work during a snowstorm, they would be very appreciated. And you would always have them with you, ready to be unrolled and tightened into action. Yet they would add very little weight and bulk.

A simple day pack is a thing a beauty. I rarely leave home without mine. The ideal day pack for me would be the MEC Klettersac shown above, but with even more gadgets removed. I would eliminate the coated nylon (the coating just flakes off after a few years, and anyway you can't trust your thousand dollar laptop to anything less than a provably watertight plastic bag), the top pocket/flap and the two straps that hold it down (with good pant pockets, I've stopped using it), the back foam (careful packing of contents eliminates the need for it), and whatever other gadgets I cut off immediately after purchase and which I've now forgotten.

Such a stripped-down daypack, on top of being very light, would also be more packable. I would stick it in my large coat pockets. Also, in the wintertime, the day pack must be considered part of the clothing! The temperature differences between outside and inside, or even between outside waiting for a bus and outside cycling up a hill, mean that you need to be able to take off and carry a large quantity of clothes.

Polochon hanging on wall.

Expedition backpacks are another topic. I've owned several of them: external frame (Camp Trails), internal frame (Lowe), etc. For a VeloHobo (as well as for normal mortals who work for a living and who don't have much time to go camping or mountain climbing), I think I'd prefer just one huge duffel bag with a separate, solid, large-wheeled dolly to carry it. See Le Polochon (French only for now) for my attempt at building a first prototype of this.

See My dream bicycle.

Most of the rest of the VeloHobo clothing and gear is already available at the MEC (or in ordinary department stores, as for socks and underwear, etc.). There are a few items I would like to see:

12.1) Dolly. There are plenty of rugged dollies that can carry a hundred kilograms (with wide, inflatable tires), and also plenty of lightweight aluminum foldable dollies too. But I've never seen one that combined both advantages. Dollies are useless on a mountain ridge or in a kayak, but bloody useful just about everywhere else! I think it's a very underestimated piece of outdoor equipment. If I was in charge of equipping an army, I think I'd supply every infantryman with one of them. See The "Hand-truck/Bike Trailer" Combo (French only for now) for my attempt at a first prototype.

The "Hand-truck/Bike Trailer.

12.2) Kerosene wick stove. I wish I had taken a picture of the kerozene wick stove I had several years ago. It was the simplest, hottest, quietest stove I've ever used. One cylindrical wick sandwiched between two perforated metal cylinders (so that air was supplied from both sides of the wick). I'm certain a very small and lightweight version could be built. Maybe it's already available somewhere?

To save our planet, it's important that as many people as possible walk and ride their bicycles, instead of driving. In nordic countries like Canada, one of the factors keeping people in their cars is the lack of high-quality, reasonably-priced clothing and gear. The Mountain Equipment Coop could continue fighting against this factor by "planting a piton into the slippery slope of fashion": the VeloHobo outdoor urban clothing and transportation system. This "piton" or benchmark would guarantee Canadians (including Canadian homeless persons, who deserve the MEC's attention more than birds and trees) a stable supply of appropriate clothing and gear. Without this "piton", the negative "Boudoir Effect" could make the MEC slide down into the crevasse of an ordinary department store.

In conclusion, it would be nice if the MEC's Board of Directors made public its reaction to this article. I will be more than happy to post e-mails from the Directors at the end of this article. I'll also gladly incorporate any clothing and gear suggestions from MEC members who happen to read this article, just e-mail them to me. Finally, maybe the MEC could improve this "VeloHobo" project and put it on the MEC web site, to poll all members about their opinion?

After I wrote this article I immediately sent it to the MEC Board of Directors, with no response of course. All I got was an e-mail from a peon requesting that I remove the MEC logo from the top of this article. (So I had to go take a picture of the outside of the MEC store in Quebec City to replace it; see first picture at the top of this article.)

With the hindsight of many years, I realized this article became my "marching orders" for the outdoor equipment I wanted to build for myself. So it looks like eventually "veloclodo" will see the light, just not at the MEC!

A kind gentleman sent me an interesting US Army report: "Spacer Systems For Cooling By Natural Convection Inside Clothing", by Lyman Fourt, June 1960, Natick, Massachusetts. Here are some excerpts:

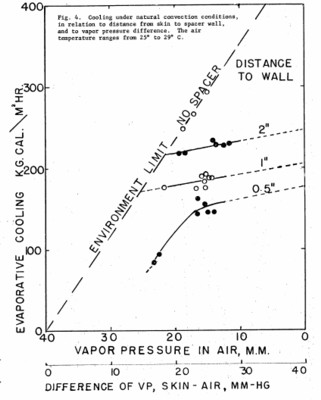

Fig. 4: Cooling under natural convection conditions

The amount of air movement which can be obtained by natural convection

depends on the difference in density between the air in the environment

and saturated air at skin temperature. This means that there is a range

of combinations

of vapor pressure and temperatures for which there will be little or no

air movement, but with air temperatures as much as 5 degrees Celcius

below body temperature, and vapor pressure differences of 25 mm, sufficient

movement is obtained to give 150Kg cal m*m hr of cooling.

Channel size or clearance is the most critical design factor in securing

cooling. Clearances of two inches are as effective as no clearance at

all, (or even somewhat better, with a relatively long chimney); one inch

is nearly as good, but with the channel reduced to a half an inch clearance

there is considerable loss of cooling. Increase of channel length lowers

the average rate of cooling, but gain from the greater length

exceeds the loss of effectiveness of the upper parts of the channel. Extra

length is much more effective in channels with one inch clearance than in

half inch clearance.

Laboratory tests of motion of the "body" inside the spacer show a decrease

of cooling, compared with undisturbed natural convection, or a small

gain, when a flexible diaphragm is used to make the motion produce flow

in and out instead of merely mixing the air inside the spacer.

[Summary, p. 1]

It is important to note that there is a set of conditions at which the

saturated air at body temperature can have the same density as the

environment, so that there will be no air movement. [...]

Unfortunately, such environments are not uncommon, so that clothing

design permitting voluntary forced ventilation will be a valuable

addition to providing space for natural convection.

[p. 3]

This suggests that channels in clothing certainly should not have less

than 0.5 inch clearance, and that one inch clearance would be a

practical compromise

[p. 9]

A means of increasing air flow and exchange with the environment which

could be used in clothing is to divide the enclosed space into at least

two parts, by a flexible diaphragm set at right angles to the line

of motion. [...] Increases in evaporation on the order of 10% are obtained

[...] To use such a system in clothing would require some connection

between the outer shell and underwear or other garments close to the

skin. This would be a special problem in clothing design and maintenance.

[p. 12]

Let's assume we want rain gear to be composed of two layers, one outer layer that is just plain nylon or some other uncoated, abraison-resistant material, and one inner waterproof layer, perhaps not unlike some cheap translucid disposable vinyl rainwear. How do we keep the waterproof layer sufficiently far away from the body to permit ventilation by natural convection?

I guess engineers at this point would draw up a "Solution Matrix", something like:

A2.1) Either the waterproof layer insures its own separation, or it doesn't. If it insures it's own separation (like, for example, a rigid cylinder of plastic), it would probably be too heavy and impossible to walk around in.

A2.2) If the waterproof layer doesn't insure its own separation, it can either be pushed away from the body, or pulled away from it.. Note that nothing prevents part of the layer to be pushed away, and part pulled, or even both at the same time.

A2.3) If the waterproof layer is pushed away from the body, it can be by internal positive air pressure, or not. In theory, you could put two big fans at the bottom of the pant legs, and product an internal positive air pressure which would keep the waterproof layer away from the body. This obviously would be impractical, but for some applications it makes sense. I seem to remember workers in bacteriological warfare laboratories who have airtight suits that are "blown up". So for hiking this idea seems a dead end.

A2.4) If the waterproof layer is not pushed away from the body by internal positive air pressure, it can be pushed away by something rigid, or not. If it's rigid, it will probably interfere with walking, or be dangerous if you fall on it, etc. This method is probably the best when you don't have to move. For example, self-supporting tents use it (the bent fiberglass poles push the tent away from the bodies inside). So for hiking this idea seems a dead end.

A2.5) If the waterproof layer is pushed away from the body by something not rigid, then things get complicated. What would push it away? Foam "sausages" like the pictures above? Air-inflated "sausages"? I once tried to make a "ventilation vest" (inspired by the "wood-bead seat covers" used by some taxi drivers) with practice golf balls (they are very light, full of holes on the outside and empty inside so they allow the passage of air, hard to crush, water-repellant so they don't absorb your sweat, have no sharp edges so they won't hurt you when you put them in between your back and a heavy backpack, apparently large enough to provide a sufficient volume of air flow between your skin and the waterproof layer, etc.). I don't remember why it failed. Maybe a combination of horrendous bulk when not in use (ideally, those practice golf balls should probably have been several times smaller in diameter), and sheer lack of balls (to make a practical ventilation vest, or practical ventilation pants, you need a lot of such balls)? I wish I could manufacture or buy large quantities of some kind of small "practice golf balls" (or some other shape that avoids hurting the human body, while also allowing air flow and pushing the waterproof layer away from the skin even under load) for more tests.

A2.6) If the waterproof layer is pulled away from the body, then things get complicated. We've already eliminated fully rigid "things", but conceptually it's useful to think about "crinolines". A crinoline is "the name given to the spring steel hoop set into a petticoat or unto cloth strips to hold the petticoats and skirts away from the body in a bell shape". If, for example, the waterproof layer has little velcro patches that attach it to the outer layer, and if the outer layer has some sort of "crinoline", then the inner layer will be pulled away from the body.

My best guess right now is a combination of A2.5 and A2.6, plus some kind of "one-way valve" mechanism to permit body-motion induced air flow.

Maybe two main "crinolines", one just below the belt line, and one around the neck area? If you think about a real skirt equipped with a real crinoline, you have something high to which the skirt is attached (the hips), and below you have the crinoline which pushes the material away from the body. By putting a second hoop in the neck area, you would have the head that would "suspend" the rain coat, and the neck crinoline that would push it away from the body. The hot air would escape through the pocket slits (for the pants), and through the sides of the face hood (probably for the pants and the coat).

If those crinolines were made of air-inflated "sausages" (think of a bicycle inner tube), then many advantages would follow: (i) you couldn't injure yourself by falling on them; (ii) when deflated, they would be unobstrusive (either to pack your rain gear tightly, or if you didn't need them in the cold weather, or to sleep on a park bench if your are a hobo, etc.); (iii) they would probably be fairly light; (iv) it might be possible to design the valves so they would open when the pressure increased too much (like if you fell on the ground), to avoid breaking the crinolines; (v) it's low technology (same technology as the cheap vinyl inflatable swimming aids you can buy for your kids at a dollar store); (vi) the crinolines might be integrated with the waterproof layer (which would probably also be airproof). This might reduce weight and manufacturing costs, and since the waterproof layer would be inexpensive and somewhat "disposable", leaks wouldn't be too much of a problem.

Perhaps other "secondary crinolines" would be necessary at the knee and elbow joints, and maybe also at the wrists and pant bottoms? And how could we make those "one-way valves"?

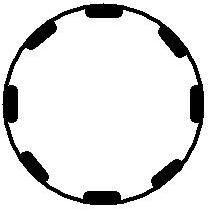

The crinolines don't have to be shaped like nice hoops. Their diameter could vary, so that air would continue to flow past them, even when they were pressed against the body:

Conceptual shape of an inflatable crinoline

I also like the idea of attaching the waterproof layer to the outer layer with little patches of velcro. These velcro patches could be glued to the waterproof layer (instead of snap buttons which could puncture the layer and require extra manufacturing steps). Also, the outer layer is naturally more rigid than the inner layer, since it's made of a solid, abraison-resistant material, and since it contains all the drawcords, pockets, and other accessories. This outer layer would not be fully rigid, but it could still "pull away" the inner layer at least a little bit. In combination with a few well-placed crinolines, it might work!

Let's Adore Jesus-Eucharist! | Home >> Varia >> Bachelor's Kit