"Who Speaks Truly?" The Magazine of those who refuse to believe

that truth doesn't exist in Philosophy and Politics.

Let's Adore Jesus-Eucharist! | Home >> Politics

"Who Speaks Truly?" The Magazine of those who refuse to believe

that truth doesn't exist in Philosophy and Politics.

If I were to participate in the foundation of a magazine, how would I go about it? What name might this magazine have? What could its fundamental orientation be? How might we proceed to write its articles?

The name of the magazine, "Who Speaks Truly", and its slogan, "The magazine of those who refuse to believe that truth doesn't exist in Philosophy and Politics", summarizes many important ideas.

Firstly, the magazine doesn't have some vague and academic name like "The Eternal Discussion", since we don't want to "shovel clouds" while drinking beer. As we speak, children are dying in countries ravaged by war, millions of families are living in abject poverty (sometimes even close to us), our environment is being destroyed by pollution, our grandchildren are being saddled with our financial irresponsibility, and so on. We must act, and the fundamental orientation of our magazine is therefore concrete action.

But to act effectively, we must act in great numbers, and with cohesion. The traditional word to describe that type of action is "Politics" (even if that word isn't popular in certain circles). And to do good Politics, we must solve the big problems, or at least mitigate them. But to solve a problem, we need to understand it thoroughly, which is another way of saying we need to know it through its ultimate causes. The traditional word to describe that type of knowledge is "Philosophy". Our magazine will therefore mostly talk about Philosophy and Politics.

These days, the word "truth" isn't fashionable, even less so when the topics are Philosophy or Politics! Nevertheless, and in a slightly provocative way, we refuse to believe that truth doesn't exist. Notice we're not establishing our magazine on a kind of "act of faith" in reason and in truth! On the contrary, our position is simply the result of repeated observations. Each time we've come across someone who believed that truth didn't exist, and that we had a "mini-debate", that person didn't look good:

"Truth doesn't exist!"

"So, the statement «Truth doesn't exist» is true, or false?"

"Oops! My car is double-parked! Good bye!"

Or something like:

"You have your reality, and I have my reality."

"OK, let's go on the side of the street, and when in my reality, I'll see a car coming toward us full speed, I'll stay on the sidewalk. But you, since you're in another reality, you'll be able to cross the street."

"Mmmmm, well, jeepers, sometimes we're inside the same reality."

Or something like:

"There is no truth in Ethics. After all, from the IS ("sein" in German), we cannot infer the OUGHT ("sollen" in German)."

"OK, give me your hand. I'll cut off of one of your fingers. After all, from the IS of your hand, you can't infer that your finger OUGHT to stay attached to it."

"No! Stop! It's truly bad to want to do that!"

And so on. (This is discussed elsewhere, like the explanation for the palm of The Philosopher's Glove, and paragraph #2 of Concedo, Nego, Distinguo.)

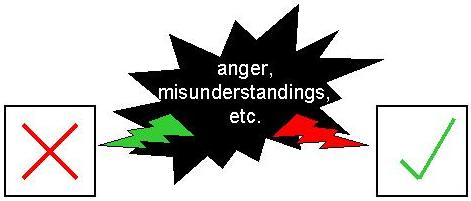

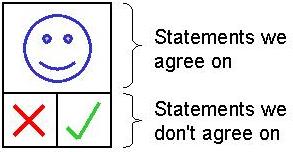

The logo summarizes the approach used to write the articles of this magazine. The starting situation, between people who have different opinions, often looks like this:

After having made an effort to find at least a few common statements on which we agree, the situation improves in at least two ways. Firstly, the "quantity of disagreement" is reduced, and secondly a kind of "bridge" is established between the diverging opinions:

Notice we don't claim to be able to eliminate all disagreements! Also notice that the three boxes of the logo look like the page formatting of the magazine's articles, where we put the common statements first, to show clearly that the authors made the effort of talking to each other before describing what separated them.

We seem to live in a society where people can increasingly express themselves, but where there are relatively few debates. Newspapers publish diverging opinions, but the authors of those opinions never have the opportunity of finding the common ground before talking about their divergences of opinion. Some TV and radio shows present "debates", but they are mostly "sound and light" shows, where they insist on the clash of conflicting points of view, and the emotions that are stirred up, in order to increase their ratings. And what can we say about Internet blogs, where anybody can say anything, without ever being confronted neither to other opinions, nor to the facts!

Personally, I wouldn't pay to subscribe to a magazine like "The Eternal Discussion". I already have too much to read. What's the use of having yet another cacophony of discordant opinions, which haven't even made the effort of talking to each other before asking me to invest my precious time to read their disarticulated articles?

On the other hand, I'd be willing to pay for a "value-added" magazine. The more there are authors, the more those authors will have radically opposed ideas, the more these ideas will concern important philosophical and political problems, and the bigger the "common ground" between all these authors, the more I'll be willing to pay.

Ah? You don't entirely agree with that statement? Excellent, let's go have a hot chocolate together, in order to have a discussion about this!

A few tips based on my limited experience:

a1.1) Don't expect miracles. An intelligent debate requires much time, charity and effort.

a1.2) Rules of the debate. Make sure you all agree from the start on the rules of the debate. I suggest: "Concedo, Nego, Distinguo", and of course this very article ("Who Speaks Truly?")

a1.3) Color in green as many things as possible on the other side. Carefully read what your opponent has written on his side, and try to find as many statements with which you agree. Then, ask permission to promote them to the "Concedo" section.

For some sentences, it will be easy to just declare "Concedo". But the interesting and productive activity is to not only agree with the obviously agreeable stuff, but also to find green or "Concedo" chunks where there apparently isn't any (or not much, anyway). There are many tricks which can help you do this, all based on the idea of the "Distinguo". Often, getting the other person to define a key term will clear up a misunderstanding. You can also cut sentences, to accept only a portion of them, or deftly add little keywords, like "if" or "ceteris paribus", which will let you make some statements acceptable to you.

a1.4) Don't debate in the tripartite grid. The tripartite (or three-part) grid described above MUST NOT be used for the actual debate. Think about the three-part grid as a fragile showcase of finished products, not the actual workshop where those products are manufactured, a workshop filled with shavings, and tools, and missed attempts tossed in a corner for recycling, etc. The actual debate should be, for example, in the e-mails exchanged between participants.

The tripartite grid should be modified only as a collaboration between all participants. For example, you carefully read the latest e-mail sent by your opponent, you mark out something you agree with, and suggest it be promoted to the "Concedo" section of the tripartite grid. If your opponent agrees in writing, then you can modify the three-part grid.

a1.5) Summarize what you disagree with. When you've found a specific point of disagreement, it's more polite and logical to first summarize your opponent's position on your side, to show you've understood it. (This helps avoid the sadly common phenomenon of the "Deaf Man's Dialogue".) After that, you can present your arguments against his position.

a1.6) Keep a copy of the "raw" arguments. The tripartite grid should be the summary of your exchanges, the part that others will read with pleasure and profit. But it's also good to keep an archive of everything that was said to get there (for example, all the e-mails), in case there should be a protest.

Mr. Andrew J. Fletcher and Ms. Marie-Claude Bisson supplied the ideas,

and

![]()

(Erden Degertas or "Tshadash") supplied the hot chocolate.

Let's Adore Jesus-Eucharist! | Home >> Politics