[Source]

Let's Adore Jesus-Eucharist! | Home >> Lost Sermons

[Source]

The following is a combination of two articles, Why the Church Cannot Reverse Past Teaching on Capital Punishment (2017-June-17) and Why the Death Penalty is Still Necessary (2017-June-18), published originally on The Catholic World Report, written by Edward Feser and Joseph M. Bessette, the authors of the excellent book By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment (Ignatius, 2017)

Edward Feser and Joseph M. Bessette.

The highly perfectible French translation of this page is to be blamed only on me.

Pope St. John Paul II was well-known for his vigorous opposition to capital punishment. Yet in 2004, then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger -- the pope's own chief doctrinal officer, later to become Pope Benedict XVI -- stated unambiguously that:

[I]f a Catholic were to be at odds with the Holy Father on the application of capital

punishment [...] he would not for that reason be considered unworthy to present

himself to receive Holy Communion. While the Church exhorts civil authorities [...]

to exercise discretion and mercy in imposing punishment on criminals, it may still be

permissible[...] to have recourse to capital punishment. There may be a legitimate

diversity of opinion even among Catholics about [...] applying the death

penalty [...]

Worthiness

to Receive Holy Communion: General Principles, (emphasis added)

How could it be «legitimate» for a Catholic to be «at odds with» the pope on such a matter? The answer is that the pope's opposition to capital punishment was not a matter of binding doctrine, but merely an opinion which a Catholic must respectfully consider but not necessarily agree with. Cardinal Ratzinger could not possibly have said what he did otherwise. If it were mortally sinful for a Catholic to disagree with the pope about capital punishment, then he could not «present himself to receive Holy Communion.» If it were even venially sinful to disagree, then there could not be «a legitimate diversity of opinion even among Catholics.»

The fact is that it is the irreformable teaching of the Church that capital punishment can in principle be legitimate, not merely to ensure the physical safety of others when an offender poses an immediate danger (a case where even John Paul II was willing to allow for the death penalty), but even for purposes such as securing retributive justice and deterring serious crime. What is open to debate is merely whether recourse to the death penalty is in practice the best option given particular historical and cultural circumstances. That is a «prudential» matter about which popes have no special expertise.

We defend these claims in detail and at length in our book By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment. What follows is a brief summary of some key points.

The Church holds that scripture is infallible, particularly when it teaches on matters of faith and morals. The First Vatican Council teaches that scripture must always be interpreted in the sense in which the Church has traditionally understood it, and in particular that it can never be interpreted in a sense contrary to the unanimous understanding of the Fathers of the Church. [Vatican I, Session 3, chapter 2, par. 6-9 and Canon 2, par. 4; Dei Verbum, #11, CCC, #107]

Both the Old and New Testaments teach that capital punishment can be legitimate, and the Church has always interpreted them this way. For example, Genesis 9:6 famously states: «Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed; for God made man in his own image.» The Church has always understood this as a sanction of the death penalty. Even Christian Brugger, a prominent Catholic opponent of capital punishment, admits that attempts to reinterpret this passage are dubious and that the passage is a «problem» for views like his own. [1]

St. Paul's Letter to the Romans teaches that the state «does not bear the sword in vain [but] is the servant of God to execute his wrath on the wrongdoer» [Rm 13:4]. The Church has always understood this too as a warrant for capital punishment, and by Brugger's own admission, there was a «consensus» among the Fathers and medieval Doctors of the Church that the passage was to be understood in this way [2]. But in that case, attempts to reinterpret the passage cannot possibly be reconciled with a Catholic understanding of scripture.

Not only Genesis 9:6 and Romans 13:4 but also passages like Numbers 35:33, Deuteronomy 19:11-13, Luke 23:41, and Acts 25:11 all clearly regard capital punishment as legitimate when carried out simply for the purpose of securing retributive justice. The lex talionis («law of retaliation») of Exodus 21 and Leviticus 24 is also obviously a matter of exacting retribution for its own sake. Deuteronomy 19:19-21 talks of execution as a way of striking «fear» in potential offenders, and deterrence is clearly in view in Romans 13:4. Hence scripture clearly teaches that capital punishment can in principle be legitimate for the sake of deterrence.

The Church has always regarded the Fathers as having an extremely high degree of authority when they are agreed on some matter of faith or morals. Now, some of the Fathers preferred mercy to the use of capital punishment. However, every one of the Fathers who commented on the subject nevertheless also allowed that capital punishment can in principle be legitimate. For example, in his Homilies on Leviticus, Origen teaches that «death which is inflicted as the penalty of sin is a purification of the sin itself.» Clement of Alexandria says that «when one falls into any incurable evil[...] it will be for his good if he is put to death.» In his commentary On the Sermon on the Mount, Augustine writes that «great and holy men[...] punished some sins with death [...] [by which] the living were struck with a salutary fear.» Jerome taught that «he who slays cruel men is not cruel.»

It is sometimes claimed that Tertullian and Lactantius were exceptions to the patristic consensus on capital punishment as legitimate at least in principle, but even Brugger admits that this is not in fact the case [3]. And again, the Fathers also uniformly regarded scripture as allowing capital punishment, and the Church teaches that the Fathers must be followed where they agree on the interpretation of scripture.

Like scripture, the Fathers also speak of capital punishment as in principle legitimate for purposes like the securing of retributive justice and deterring others. (Indeed, neither scripture nor the Fathers refer to protection against immediate physical danger even as a purpose of capital punishment, let alone as the only legitimate purpose.)

The Church has also regarded the Doctors of the Church as having a very high degree of authority when they are agreed on some matter of faith or morals. Like the Fathers, these Doctors -- including thinkers of the stature of St. Thomas Aquinas, St. Robert Bellarmine, and St. Alphonsus Ligouri -- are all in agreement on the legitimacy in principle of capital punishment. Aquinas even dismissed as «frivolous» the suggestion that capital punishment removes from offenders the possibility of repentance, arguing that «if they are so stubborn that even at the point of death their heart does not draw back from evil, it is possible to make a highly probable judgment that they would never come away from evil to the right use of their powers» [Summa Contra Gentiles, III, 146].

No pope from St. Peter to Benedict XVI ever denied the legitimacy in principle of capital punishment, and many popes explicitly affirmed its legitimacy, even as a matter of basic Catholic orthodoxy. For example, Pope St. Innocent I taught that to deny the legitimacy of capital punishment would be to go against biblical authority, indeed «the authority of the Lord» himself. Pope Innocent III required adherents of the Waldensian heresy, as a condition for their reconciliation with the Church and proof of their orthodoxy, to affirm the legitimacy in principle of capital punishment. Pope St. Pius V promulgated the Roman Catechism, which states that:

Another kind of lawful slaying belongs to the civil authorities, to whom is entrusted power of life and death, by the legal and judicious exercise of which they punish the guilty and protect the innocent. The just use of this power, far from involving the crime of murder, is an act of paramount obedience to this Commandment which prohibits murder.

The 1912 Catechism of Christian Doctrine issued by Pope St. Pius X says in the context of discussion of the Fifth Commandment: «It is lawful to kill[...] when carrying out by order of the Supreme Authority a sentence of death in punishment of a crime.» Pope Pius XII taught that «it is reserved[...] to the public authority to deprive the criminal of the benefit of life when already, by his crime, he has deprived himself of the right to live.»

It is sometimes alleged that while Pope John Paul II did not contradict past teaching, he did modify doctrine on capital punishment in a more restrictive direction in the catechism which he promulgated. In particular, it is claimed by some that John Paul taught that it is in principle immoral to resort to capital punishment except for the purpose of protecting others against the immediate physical danger posed by an offender. However, then-Cardinal Ratzinger explicitly denied that there was any change at the level of doctrinal principle. He affirmed that «the Holy Father has not altered the doctrinal principles which pertain to this issue» and that the revisions to the catechism reflected merely «circumstantial considerations [...] without any modification of the relevant doctrinal principles.» [4]

Moreover, as Cardinal Avery Dulles has pointed out, had the pope made such a modification to doctrine, he would have been partially reversing or contradicting previous teaching rather than merely modifying it [5]. For as we have noted, scripture and the Fathers teach that capital punishment can be legitimate specifically for purposes of retribution and deterrence, and not merely for the purpose of counteracting some immediate physical threat.

Like other recent popes, [Bergoglio] has opposed the use of the death penalty. But there are indications that, unlike any previous pope, [Bergoglio] may be inclined to declare capital punishment intrinsically immoral. For example, in a recent statement, [Bergoglio] said that «the commandment 'Thou shalt not kill' has absolute value and applies both to the innocent and to the guilty» (emphasis added). It has also been reported that he has set up a commission to explore changing the Catechism of the Catholic Church so that it will «absolutely» forbid capital punishment.

Does Catholic doctrine permit a pope to make such a change? It very clearly does not. The First Vatican Council explicitly taught that:

[T]he Holy Spirit was promised to the successors of Peter not so that they might,

by his revelation, make known some new doctrine, but that, by his assistance, they

might religiously guard and faithfully expound the revelation or deposit of faith

transmitted by the apostles.

Decrees

of the Vatican I Council,

Session 4, Chapter 4, Paragraph 6

(Emphasis added)

And the Second Vatican Council explicitly taught that:

[T]he task of authentically interpreting the word of God, whether written or handed

on, has been entrusted exclusively to the living teaching office of the Church[...]

This teaching office is not above the word of God, but serves it, teaching only

what has been handed on [...]

Dei Verbum,

Chapter 2, paragraph 10

(Emphasis added)

If [Bergoglio] were to teach that capital punishment is «absolutely» immoral, he would be contradicting (rather than «religiously guard[ing],» «faithfully expound[ing],» and «hand[ing] on») the teaching of scripture, the Fathers, and all previous popes, and substituting for it «some new doctrine.» He would be overruling the many scriptural passages that support capital punishment, thereby putting himself «above the word of God.» If he were to claim warrant for this novel teaching in the commandment against murder, he would be contradicting the way every previous pope who has addressed the subject has understand that commandment. As we have seen, Pope Pius XII teaches that the guilty person «has deprived himself of the right to live,» and the catechisms promulgated by Pope St. Pius V and Pope St. Pius X explicitly affirm that capital punishment is consistent with the commandment against murder.

Moreover, if [Bergoglio] were to teach that capital punishment is intrinsically immoral, he would undermine the authority of Catholic teaching in general. As Cardinal Dulles wrote:

The reversal of a doctrine as well established as the legitimacy of capital punishment would raise serious problems regarding the credibility of the magisterium. Consistency with Scripture and long-standing Catholic tradition is important for the grounding of many current teachings of the Catholic Church; for example, those regarding abortion, contraception, the permanence of marriage, and the ineligibility of women for priestly ordination. If the tradition on capital punishment had been reversed, serious questions would be raised regarding other doctrines [...] [7]

Indeed, a change vis-à-vis the death penalty would undermine the pope's own credibility as well. Cardinal Dulles continues:

If, in fact, the previous teaching had been discarded, doubt would be cast on the current teaching as well. It too would have to be seen as reversible, and in that case, as having no firm hold on people's assent. The new doctrine, based on a recent insight, would be in competition with a magisterial teaching that has endured for two millennia -- or even more, if one wishes to count the biblical testimonies. Would not some Catholics be justified in adhering to the earlier teaching on the ground that it has more solid warrant than the new? The faithful would be confronted with the dilemma of having to dissent either from past or from present magisterial teaching.

It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that, were [Bergoglio] to condemn capital punishment as intrinsically immoral, he would thereby be joining the ranks of that very small number of popes who have taught doctrinal error (which is possible when a pope does not speak ex cathedra).

However, we do not believe that [Bergoglio] will do this. For one thing, as is well known, [Bergoglio] is prone in his public utterances to making imprecise and exaggerated statements. He has certainly done so before when speaking about capital punishment. For example, in a statement from March 15, 2015, [Bergoglio] approvingly cited some lines he attributed to Dostoevsky, to the effect that «to kill one who killed is an incomparably greater punishment than the crime itself. Killing in virtue of a sentence is far worse than the killing committed by a criminal.»

Consider a serial killer like Ted Bundy, who murdered at least fourteen women. Bundy routinely raped and tortured his victims, and also mutilated, and even engaged in necrophilia with, some of their bodies. He was executed in the electric chair, a method of killing that takes only a few moments. Should we interpret [Bergoglio] as seriously suggesting that Bundy's execution was «far worse» and an «incomparably greater» crime than what Bundy himself did? Surely not; such a judgment would be manifestly absurd, and indeed, frankly obscene. Surely [Bergoglio] did not intend to teach such a thing, but was rather merely indulging in a rhetorical flourish. A charitable interpretation of some of his other remarks about capital punishment would lead us to conclude that he does not intend to contradict the tradition.

For another thing, if [Bergoglio] has indeed set up a commission to study revising the catechism, that in itself indicates that he wants to be careful not to contradict past teaching. Presumably, Cardinal Gerhard Müller, current prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, would play a key role on such a commission. Commenting on the controversy [Bergoglio]'s remarks on various subjects have sometimes generated, Cardinal Müller has noted that «[Bergoglio] is not a 'professional theologian', but has been largely formed by his experiences in the field of the pastoral care» [8]. Asked if he has sometimes had to correct [Bergoglio]'s remarks from a doctrinal point of view, the cardinal replied: «That is what he [Bergoglio] has said already three or four times himself, publicly [...]» Cardinal Müller also emphasized that [Bergoglio] himself «refers to the teaching of the Church as the framework of interpretation» for his various remarks. In another interview in which he was asked about [Bergoglio]'s sometimes doctrinally imprecise statements, Cardinal Müller acknowledged that churchmen sometimes «express themselves in a somewhat inappropriate, misleading or vague way,» and that not all papal pronouncements have the same binding nature. [9]

Having shown here that Catholic teaching has always supported the legitimacy of capital punishment, in [the next] part of this article we will discuss some of the reasons for believing that it remains necessary for achieving public safety and the larger common good.

As we showed [here above in] this essay, for two millennia the Catholic Church has taught that the death penalty can be a legitimate punishment for heinous crimes, not merely to protect the public from the immediate danger posed by the offender but also to secure retributive justice and to deter serious crime. This was the uniform teaching of scripture and the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, and it was reaffirmed by popes and also codified in the universal catechism of the Church promulgated by Pope St. Pius V in the sixteenth century, as well as in numerous local catechisms.

Consider the standard language of the Baltimore Catechism, which was used throughout Catholic parishes in the United States for educating children in the faith for much of the twentieth century:

Q. 1276. Under what circumstances may human life be lawfully taken?

A. Human life may be lawfully taken: 1. In self-defense, when we are unjustly

attacked and have no other means of saving our own lives; 2. In a just war, when

the safety or rights of the nation require it; 3. By the lawful execution of a

criminal, fairly tried and found guilty of a crime punishable by death when the

preservation of law and order and the good of the community require such

execution.

[10]

Thus, killing another human being in self-defense, during a just war, or through the lawful execution of a criminal does not violate the Fifth Commandment's rule «Thou shall not kill» (which many modern editions of the Bible translate as «Thou shall not murder»). The permissibility of these three types of lawful killing (unlike the deliberate killing of the innocent, which is always prohibited) depends on contingent circumstances. As long as (in the words of Pope Innocent III) «the punishment is carried out not in hatred but with good judgment, not inconsiderately but after mature deliberation,» the death penalty may be imposed if it genuinely serves the common good.

Generally, the Church has left these and similar prudential judgments to public officials. For example, the current Catechism of the Catholic Church expressly affirms that when it comes to judging whether a decision to go to war is morally justified, «the evaluation of these conditions for moral legitimacy belongs to the prudential judgment of those who have the responsibility for the common good.» [CCC, #2309]. The institutional Church respects the authority and responsibility of public officials, guided by the sound moral principles it preserves and promulgates, to make these judgments. Similarly, to the best of our knowledge, the Church has fully respected the authority of lawmakers to write statutes on self-defense that detail the conditions under which individuals may use force, including deadly force, to protect themselves and others.

Unfortunately, in recent years churchmen have not been equally respectful of the authority and duty of public officials to exercise their prudential judgments in applying Catholic teaching when it comes to the death penalty, despite the fact that churchmen bring to the debate over capital punishment no particular expertise derived from their religious training and pastoral experience. Given the Church's longstanding and irreformable teaching that death may in principle be a legitimate punishment for grievous crimes, the key issue for Catholics is the empirical and practical question of whether the death penalty more effectively promotes public safety and the common good than do lesser punishments. We maintain that it does and thus devote about half of our book, By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A Catholic Defense of Capital Punishment to making this case [11].

The current Catechism of the Catholic Church affirms that «[l]egitimate public authority has the right and the duty to inflict punishment proportionate to the gravity of the offense» and that «[p]unishment has the primary aim of redressing the disorder introduced by the offense.» [CCC, #2266] Thus, punishment is fundamentally retributive, inflicting on the offender a penalty commensurate with the gravity of his crime, though it may serve other purposes as well, such as incapacitating the offender, deterring others, and promoting the offender's rehabilitation.

The significance of this point cannot be overstated. Secular critics of capital punishment often reject the very idea of retribution -- the principle that an offender simply deserves a punishment proportionate to the gravity of his offense -- but no Catholic can possibly do so. For unless an offender deserves a certain punishment -- whether that be a fine, imprisonment, or whatever -- and deserves a punishment of that specific degree of severity, then it would be unjust to inflict the punishment on him. Hence all the other ends of punishment -- deterrence, rehabilitation, protection of society, and so on -- presuppose the retributive aim of giving the offender what he deserves. This is why the Catechism promulgated by Pope St. John Paul II reaffirms the traditional Catholic teaching that retribution is the «primary aim» of punishment.

Among the many reasons why capital punishment ought to be preserved (all of which we set out at length in our [now published] book), the most fundamental one is that for extremely heinous crimes, no lesser punishment could possibly respect this Catholic principle that a punishment ought to be proportional to the offense. We devote the remainder of this article to developing this point.

[Source]

In the American states today the only crime for which the death penalty may be imposed (according to U. S. Supreme Court decisions) is murder. (The Court has not ruled on the legitimacy of the death penalty for the national crimes of treason and espionage.) Western societies, both before and after the rise of Christianity, never imposed the death penalty for all unlawful killings. As far back as our records go, laws reserved the ultimate punishment for intentional and malicious killings and usually imposed a lesser punishment for negligent killings and those resulting from a «heat of passion.» The thirty-one American states with capital punishment today are even more selective, reserving the death penalty for the most heinous murders, such as multiple murders, rape murders, torture murders, and the murders of the very young and the very old.

A close analysis of the 43 murderers executed in 2012 reveals the true depravity of the crimes and the criminals that merit the death penalty in the United States today. Here are nine of the cases (space does not allow a complete listing):

- David Alan Gore, who, with his cousin, cruised central Florida in the 1970s and 1980s, abducting, raping, and murdering at least half a dozen teenage girls (and the mother of one of them). In his last murder, the 17-year-old girl, repeatedly raped by Gore, had managed to free herself and then ran naked from the house where she was being held. Gore chase down the girl, dragged her back towards the house, and shoot her twice in the head in the driveway in full view of 15-year-old boy who was bicycling past the scene.

- Edwin Hart Turner, who during a robbery shot and killed an unresisting convenience store clerk pleading for his life and then shortly thereafter robbed a customer at a gas station and shot and killed him while he was on the ground also pleading for his life.

- Robert Brian Waterhouse, who early one morning left a bar with a 29-year-old woman and later beat her with a hard instrument, raped her, and sexually assaulted her with a large object. She was alive throughout this assault. He then dragged his victim into the water where she died of drowning. She was discovered completely naked and her injuries were so severe that she was unrecognizable. Fourteen years before, Waterhouse had broken into a home and killed a 77-year-old woman, for which he served 8 years before being paroled.

- Timothy Shaun Stemple, who murdered his wife to collect her life insurance by beating her in the head with a baseball bat, driving a truck over her head, beating her again, driving the truck over her chest, and then driving over her at 60 miles per hour, killing her. While awaiting trial Stemple tried to get other inmates to arrange the death of several witnesses in his case.

- Henry Curtis Jackson, who, in an attempt to steal money from his mother's home, murdered a 2-year-old girl, a 2-year-old boy, a 3-year-old boy, and a 5-year-old girl. He injured two other older girls and stabbed a 1-year-old girl, leaving her unable to walk.

- Daniel Wayne Cook, who, with an accomplice, killed a 26-year-old man after beating, torturing, and sodomizing him over a 6-7 hour period. A few hours later the offenders sodomized and strangled to death a 16-year-old boy.

- Robert Wayne Harris, who in retaliation for his firing from a car wash, murdered the manager and four other employees by shooting them in the back of the head at close range while they were kneeling on the floor. Another survived but was left with permanent disabilities. When he was being interviewed by police about this crime, he volunteered that he had previously abducted and murdered a woman and he led police to her remains in a field.

- Richard Dale Stokley, who with an accomplice abducted two 13-year-old girls from a campsite, drove them to a remote area, raped them, stabbed them in the eye, killed them by stomping on their necks, and then threw the naked bodies down an abandoned mineshaft.

- Manuel Pardo, Jr., who killed seven men and two women in five separate incidents over a four-month period.

Altogether, the forty-three offenders executed in 2012 killed a total of 70 individuals and injured another 12 during the capital crimes for which they were executed. We also know that eight of the forty-three (19%) had previously killed at least one other person, and several had killed more than one. And many of those who had not (as far as we know) killed in the past had previously committed other very serious crimes. Altogether, at least two-thirds of those executed in 2012 had previously committed a homicide, sexual assault, robbery, felony assault, or kidnapping.

As these facts and a wealth of other data show, we reserve the death penalty in the United States for the most heinous murders and the most brutal and conscienceless murderers. This is not, as some critics argue, a kind of state-run lottery that randomly chooses an unlucky few for the ultimate penalty from among all those convicted of murder. Rather, the capital punishment system is a filter that selects the worst of the worst. Here is one particularly telling statistic: of the murders that resulted in the 43 executions in 2012, more than a third involved the rape of the murder victim or of another person either by the executed offender or his accomplice. Yet, among all homicides in the United States in recent decades, only about 1% involved a sexual assault. In nearly all of the thirty-one American states that currently have the death penalty, legislators have identified rape murder as especially heinous and thus potentially deserving a death sentence. Indeed, before someone can be executed in the United States legislators must agree that the kind of murder committed potentially merits death and prosecutors and juries must agree that this particular murderer deserves to die for his crime(s).

Put another way, to sentence killers like those described above to less than death would fail to do justice because the penalty -- presumably a long period in prison -- would be grossly disproportionate to the heinousness of the crime. Prosecutors, jurors, and the loved ones of murder victims understand this essential point. As the mother of the murder victim of one of those executed in 2012 said to the sentencing jury, «I would beg this court and this jury to see that justice is done. And justice to us is no less than the death penalty.» Even offenders themselves sometimes recognize that justice demands their death, as three of those executed in 2012 fully acknowledged. One who killed two men after a minor traffic accident said, «I killed two people. I've always accepted responsibility for the taking of their lives [...] I believe in justice and I believe that the victims, their hatred, their anger, they need to have justice.» Another who killed a 63-year-old prison guard during an escape attempt pleaded guilty and waived all appeals, resulting in his execution just one year after sentencing. In a letter he wrote a week before his execution he commended the prosecutor and affirmed the justice of his punishment: «I do not want or desire to die, instead I deserve to die; this I have always stated.» In concluding he wrote, «It's not about me or any future killers, it is about ensuring that in contested cases that the victims and their families get their intended and needed swift justice.» And one who abducted, raped, and murdered a 9-year-old girl told a federal court, «I killed the little girl. It's just that the punishment be concluded. I believe it's a good thing, that the death penalty does inhibit further criminal acts.» He added, «I killed. I deserve to be killed.»

We have focused here on the retributive purpose of the death penalty because, again, according to Catholic doctrine retribution is the «primary aim» of punishment. In By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed we also show that capital punishment has various practical benefits, such as protecting prison guards and other inmates from the most dangerous offenders, and protecting members of the community by giving «lifers» who escape from prison strong reasons not to kill while on the run. We also argue that capital punishment almost certainly deters at least some potential murderers, and gives murderers a strong incentive to plea bargain to very long prison sentences, which likely saves lives by increasing the deterrent and incapacitative effect of long prison sentences over shorter ones. (We also refute the common charges that the capital punishment system in the United States results in the execution of the innocent and discriminates against minorities and the poor.)

But make no mistake: retributive punishment in and of itself makes the world a safer place and upholds the common good:

- It powerfully reinforces society's condemnation of the crime of murder, making it less likely that those growing up in a community with the death penalty would even consider killing someone in the first place.

- It anchors the entire schedule of punishments for serious crimes to the principle of just deserts, ensuring the survival of retributive punishment as a key element in the criminal justice system and thus shoring up the schedule of punishments against powerful modern tendencies toward ever greater leniency in criminal punishment.

- It reassures the families and other loved ones of the victims of grave crimes that they live in a society that is just, and that shows respect for the lives of victims by inflicting on their killers a penalty that is truly proportionate to the gravity of the offense.

- It encourages repentance insofar as it makes offenders aware of the extreme gravity of their crimes and also of the shortness of the time remaining to them to get themselves right with God and to ask forgiveness from the families of their victims.

- Perhaps most importantly, in its supreme gravity it promotes belief in and respect for the majesty of the moral order and for the system of human law that both derives from and supports that moral order.

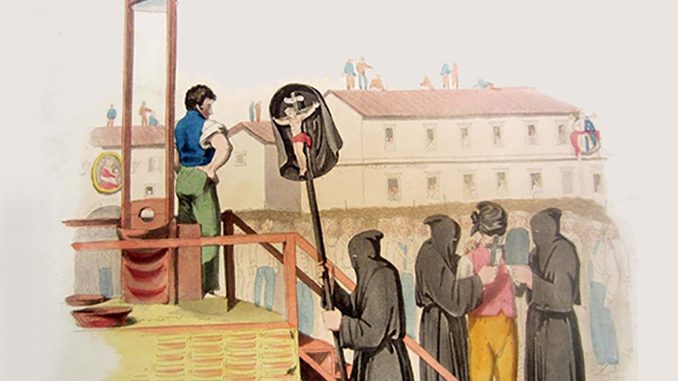

For well over a millennium the popes of the Catholic Church exercised civil authority over a large swath of territory in central Italy called the Papal States. In that capacity they frequently authorized the death penalty for murderers and others. Although we do not have data for how often they did so before the nineteenth century, we know that between 1796 and 1865, six popes authorized a total of 516 executions, four-fifths for murder.

This papal endorsement of capital punishment, though rather recent in the history of the Church, is largely ignored in Catholic debates over the death penalty, as is the striking fact that from 1929 to 1969 the criminal code of the Vatican City itself included the death penalty for the attempted assassination of the pope. The many dozens of popes who approved executions in the Papal States and the representatives of the Church responsible for the Vatican City criminal code understood a truth that too many in the modern Church have forgotten: that justice demands the death penalty for the most heinous crimes and that if «the punishment is carried out not in hatred but with good judgment, not inconsiderately but after mature deliberation,» it promotes public safety and serves the larger common good.

Copyright © 2017 Edward Feser and Joseph M. Bessette.

[1] Brugger, Capital Punishment and Roman Catholic Moral Tradition (University of Notre Dame Press, 2003), p. 73.

[2] Ibid., p. 112.

[3] Ibid., pp. 77 and 84.

[4] Response to an inquiry from Fr Richard John Neuhaus, published in the October 1995 issue of First Things.

[5] Dulles, «Catholic Teaching on the Death Penalty: Has It Changed?» in Erik Owens, John Carlson, and Eric Elshtain, eds., Religion and the Death Penalty (Eerdmans, 2004).

[6] SJJ: The authors are very professional and polite and courteous, so they always talk about "Pope Francis", not the biting "Bergoglio" I substituted everywhere. Sorry.

[7] Dulles, «Catholic Teaching on the Death Penalty: Has It Changed?», Op. cit., p. 26.

[8] Cardinal Müller's remarks were made in a March 1, 2016 interview with the German newspaper Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger. The English translation is quoted from Maike Hickson, Vatican's doctrine chief: Pope is not a "professional theologian", LifeSiteNews.com, March 14, 2016.

[9] These remarks were made in an interview in the German magazine Die Zeit, December 30, 2015.

[10] The Baltimore Catechism is available from many online sources. The death penalty is addressed in the third volume of the catechism, which is for older students. See www.baltimore-catechism.com/lesson33.htm, accessed June 4, 2015.

[11] SJJ: I can testify that, in their book, the authors dig deeply and in very minute detail into current social science about capital punishment. My conclusion, after this avalanche of statistics, is that when somebody tells you that "studies have demonstrated that the death penalty is useless/racist/discriminatory/etc", just show them your First finger, then buy them a copy of Feser and Bessette's book.

Let's Adore Jesus-Eucharist! | Home >> Lost Sermons