Let's Adore Jesus-Eucharist! | Home >> Directory of sheep and wolves

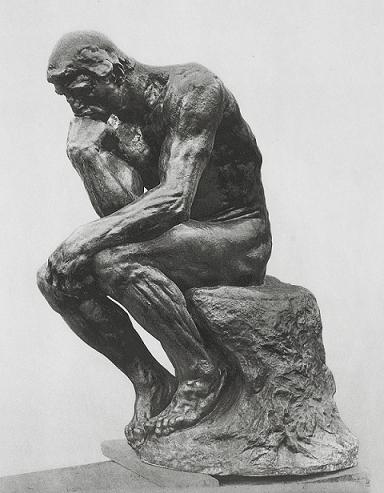

"Fortunately, I'm a good scientist and not one of those evil philosophers,

otherwise all my thoughts would be automatically false!"

(Auguste Rodin. The Thinker.

Source)

1) J. Ferenc (2008-March-30-1)

2) J. Ferenc (2008-March-30-2)

3) J. Ferenc (2008-April-03)

4) S. Jetchick (2008-April-09)

5) J. Ferenc (2008-April-13)

6) S. Jetchick (2008-April-19)

7) J. Ferenc (2008-April-21)

8) S. Jetchick (2008-May-03)

9) J. Ferenc (2008-May-04-1)

10) J. Ferenc (2008-May-04-2)

11) S. Jetchick (2008-May-05)

12) J. Ferenc (2010-Feb-06)

13) J. Ferenc (2010-Feb-13)

14) J. Ferenc (2010-Feb-21)

15) S. Jetchick (2010-Feb-23)

16) J. Ferenc (2010-Feb-23)

17) J. Ferenc (2010-Feb-26)

18) J. Ferenc (2010-Feb-26-2)

19) S. Jetchick (2010-March-17)

20) J. Ferenc (2016-October-12)

-----Original Message----- From: J. Ferenc Sent: 30 mars 2008 14:24 To: stefan.jetchick Subject: Dear Stefan Jetchick (Re: Science questions) Dear Stefan Jetchick, My name is Jason Ferenc. I find your website charming; if I could make facial expressions as lively as yours, I could go into theater! I work with your [...] of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, where I am an undergraduate. The conversation one day drifted onto the subject of your website, to which I went, and with which I have become increasingly intrigued. I am writing to you because in your article "Isn't believing in Science anti-scientific?" you ask a series of questions about science, apparently inviting response. I would like to try to answer some of those questions with you, if you are still inclined to hear answers. I would be interested in hearing your thoughts. I fear that my answers may be too verbose, and that you will never read them. Oh, well... Question numbers are as appear in your article: 2.1) Science is any systematic means of acquiring knowledge, broadly. I think its usual use in modern speech is to refer to the system of acquiring knowledge using the experimental-or, more generally, the "scientific"-method. By the way, the latter is the sense in which I will use the word here. 2.2) I suppose one could classify knowledge into as many different types or categories as one pleases. I would argue that there is only one type of knowledge. Knowledge is knowledge, just like water is water. But is it really water in that cup? Knowledge which has been scientifically derived is better because it is testable. Science agrees that the senses are reliable, and always tries to find ways to make any knowledge testable in such a way that it-or its components-can be reliably perceived by our senses, or else to find ways to prove a thing by building upon elements which can, at some level, be oberved and verified. A superstitious belief (e.g. "If I don't walk around my bed three times with a candle and say 'Ohm, zigamwhey' five times, then at precisely midnight, my pillow will turn into a giant chicken and peck my eyes out.") can and should be tested. Once this theory has been tested scientifically (experimentally), then you might say that you now have "scientific knowledge" on that subject. The most important point, I think, is this: the superstitious knowledge could be completely true. Or it could be completely false. Or it could be partly true and partly false. The problem is, we just don't know. A system of knowledge which is infused with an unknown amount of error, and with no reasonably reliable way of separating the error from the truth, is useless. 2.3) Science does not teach truth. As Indiana Jones said, "Science seeks facts, not truth. If it's truth you're after, the philosophy class is right down the hall." Truth is the absolute reality of the universe. Again, I would argue that there is only one type of truth. The real difference is how our perception of that truth is obtained. Science does argue that since humans cannot perceive truth directly, "truth" (knowledge of truth) obtained from difference sources and using different methods may be more or less reliable. As an obvious example, there is only one truth about what your next door neighbor's house looks like (sophistical convolutions aside). I can certainly espouse an opinion about what your neighbor's house looks like, using the technical method known as "guessing," and I could conceivably be correct. You can make a statement on the same subject, using the technical method of "looking at it", and you could conceivably be wrong. But logically, information from you on the subject is likely to be far more reliable. Still: one truth, different perceptions; one statue, different vantage points. [Have you ever read St. Augustine, "On Free Choice of the Will," Book Two? I very strongly recommend it, as it addresses parts of this subject very nicely (and in about 30 pages, if my memory serves). In fact would love to hear your views on it if you have read it.] Short answer: The goal of the scientific method is to ensure that the individual has the best possible vantage point before making the observation. This ensures that our perception of the one truth is as unclouded as possible. But science does not teach truth. Science gives a method to more clearly perceive the truth, and only in those areas of knowledge amenable to physical observation. 2.4) Um, I don't know. With a typewriter? What do you mean? 2.5) Statistics are merely a collection of observations which may then be analyzed using practical mathematical principles in order to yield a complete picture of the subject of analysis. For example, if I measure the skirt length of hundreds of women walking out of a certain building, I can find the most popular skirt length. This is not the type of information which I could obtain from a single observation. It requires multiple observations. Further, the more observations I have made, the more accurate my calculated "most popular skirt length" will be. That is statistics in a nutshell. Statistics do not speak for themselves. They illustrate facts, and no more. Suppose, for example, we measure the average skirt lengths of women leaving a business tower and also an hourly-rate motel in the red light district. We find that the average skirt lengths are significantly* different. In fact, we find that the average skirt lengths of the women leaving the hourly-rate motel are often much shorter that those of the businesswomen. You might very quickly reach certain specific conclusions after having heard these facts. You might, in fact, conclude that one group of women is perhaps more sexually promiscuous than the other. But the statistics themselves don't tell us this - that is a separate conclusion which must be supported on its own evidence. *This is where statistics comes in really handy. How different is significantly different? The mathematics of statistical analysis can take two groups of data and tell us the percent probability that the differences between these groups of data would arise by chance. 2.6) Give specifics. Generally the scientific method indicates experimentation, observation, and extrapolation from experimentation. Each branch of science operates in its own field, but the concepts are very much the same. 2.7) A world-renowned book on "science" itself might be Discourse on Method by Rene Descartes. I'm not quite certain. Since science strongly discourages reliance on authority of any kind to presume the truth of statements, there is no such thing as a "Science Bible." In science, reality itself is the bible, and the books on science are just people's interpretation of that physical reality. The only stipulation is that you must "read the bible" (that is, look to physical reality for your answers). 2.8) Ah, that's what I thought you meant to begin with. Science is pretty well characterized by the scientific method. Science is simply a systematic way of obtaining an accurate perception of truth. If you want a book that is about science, but not about method, then you'll simply be looking at a catalogue of all the conclusions which have been reached using (or claiming to use) the scientific method. That is what fills libraries across the world. My own thoughts: Science looks to the observable world for its answers. It does not deny the existence of things which cannot be observed, nor does it support them. It simply does not speak on those matters. "Science," in the modern sense, is inextricably connected to the physical world. That's literally what it is all about, since the basic idea of science is that experimental results be verified by one's own senses, and from these definite results we make inferences, which lead to theories from which specific and, ideally, testable deductions can be made. Any person who dares to say anything about religion using science (aside from simply saying, "there is no evidence presently available to either support or disprove...and no foreseeable way of obtaining it.") is not a scientist, since, as I have said, science proper simply has nothing to say about things which are not a part of the natural world. Whether philosophy is "unscientific" depends upon exactly what is meant by the statement.. I am given to understand that logic is a form of philosophy. Logic is relied heavily upon to interpret the results we get from the scientific method. If, using the scientific method, we determine that Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria are only found in humans which display symptoms of tuberculosis, and if from these facts we deduce that all frogs are princes in disguise, then the facts have not done us much good, have they? Without logic, all of the experiments in the world could not yield useful conclusions. Mind, science no doubt could help to verify the conclusions to which logic leads us, and in this way logic becomes verifiable and amenable to the scientific method. I believe that often when people try to make arguments in the name of "science", they are really arguing in the name of logic (or more broadly, philosophy, or more broadly, knowledge, or more broadly, truth). Religion also argues in the name of truth. The only lesson which science teaches us in areas not directly connected to the natural world is to always keep your eye on the ball: who is in a position to perceive truth, and what likelihood do they have of being correct? Are they speaking about actual, sensible things, or are they just making wild assumptions? By the way, your neighbor's house is yellow with purple stripes. It's the truth. Yours most sincerely, J. Ferenc Amherst, Mass. P.S. - You put out a call for grammatical errors to be pointed out to you. In sec. 2.9 of "Isn't believing in Science Unscientific?" you say "world-renown."

-----Original Message----- From: J. Ferenc Sent: 30 mars 2008 22:47 To: Stefan Jetchick Subject: RE: Dear Stefan Jetchick (Re: Science questions) Dear Stefan, Good evening, and thank you for responding so incredibly promptly. Don't feel at all rushed to read my email. A big contract? As far as me being able to yank anybody out of their ignorance, I wouldn't hold my breath! I'd like to think of us as making a mutual inquiry into a subject. I haven't any problem with you posting our conversation on your website, if you want. As a general rule, I try to avoid having my name appear on the internet. You may call me ["Mr. X11" ...] or else any other name which strikes your fancy. As long as it isn't "Mr. Blockhead"!! :) By the way, in my other e-mail I state that science argues that humans cannot directly perceive truth (absolute reality). I then carelessly proceed to speak of "perceiving the truth"! Whenever I speak of perceiving truth, what I mean is "to perceive things with our senses, or with our minds, which enable us to form a mental image of the truth." Best of luck with your work! - J. Ferenc

-----Original Message-----

From: J. Ferenc

Sent: 3 avril 2008 19:56

To: stefan.jetchick

Subject: Some further thoughts on science and reality

Dear Stefan,

My apologies at sending you more drivel before you have even had the

chance to respond to my first email with a request never to email you

again!

In Section 3.6 of «Public Enemy #1: Religious Obscurantism» you

reference several people who make statements concerning science, in a

context which seems to imply that you believe the assertions are

false. Your quotes are indicated with italics. My thoughts:

3.6.1) "Elusive Truth". Karl Popper said science cannot prove a

theory is true, but only that a theory is false ("falsifiability").

"Hence, the best that science could do was to offer numerous

conjectures, refute the worst with contrary data, and accept the

survivors in a tentative manner. But that implies that although "we

search for truth, we can never be sure we have found it"" [Karl

Popper, quoted in Gauch 2003, p. 82].

But the statement is, in a way, true. All observations are true in

and of themselves, if they are accurate. But they are useful to us

as thinking creatures only inasmuch as they help us to verify

theories which will predict future occurrences and explain past ones.

It has been said, «You can prove something a thousand times, but you

only have to disprove it once.» This seems to be true, because our

experiments to prove those theories will sometimes be contaminated by

our own theories (or lack of theory).

As an example: I propose the theory that heavier objects will fall

faster than lighter objects. We have a pebble, and a piece of paper.

To demonstrate the truth of my theory, I drop the pebble and the

piece of paper from the same height at the same time. The pebble

strikes the ground first. I have just proven my theory as true in

this case. I repeat the experiment. I have proven it yet again.

You object that perhaps there is something peculiar to the properties

of rocks and feathers, and that we ought to try other objects. We

perform the experiment with a nail and a feather, having the same

results.

All afternoon we perform experiments: rock and paper, nail and

feather, rubber ball and cotton wisp, acorn and leaf.....each time

the heavier object falls faster than the lighter one. It will not be

until one of us, perhaps by chance, takes the paper and crumples it

into a ball before dropping it that we will realize that something is

wrong with the theory. This single observation has set into doubt a

theory that was seemingly proved a hundred times over. That's the

thing about theories: you can prove them correct as many times as you

like, but that does not mean that one day an observation will not be

made which will necessitate a modification of theory which had worked

so well up to that point. It is when the theory is proved wrong that

knowledge becomes modified.

3.6.2) "Underdetermined Theory". According to Popper, all

observations are "contaminated" with theory. "But if observations are

theory-laden, that means that observations are simply theories, and

then how can one theory falsify (never mind verify) another theory?

I think that Popper could have phrased his assertion a bit better. I

think I understand what he might be trying to say, though. I assert

that all observations are true, inasmuch as they are accurate. But

which observations we choose to make, and our evaluation of the

importance of these observations, can be influenced by our

preexisting theory, or our lack of a theory. As a perfect example,

in the series of hypothetical gravity experiments above, our lack of

realization of the potential effect of air resistance on the

manifestation of gravity's force caused us to neglect to control for

that variable in the design of the experiment. When we first

designed the experiment with the feather and stone, we had no idea

about air resistance; for all we knew, light had just as much of an

effect on gravity and we might have tried performing the experiment

in a darkened room. So, our own theory (or lack of theory), will

effect the observations which are made, and the significance which is

ascribed to these observations.

Curiously, the full implications of this little complication were not

fully grasped by Popper, but by Imre Lakatos: not only are scientific

theories not verifiable, they are not falsifiable either" [quoted in

Gauch 2003, p. 84].

Obviously this must be false, since part of the very definition of a

theory (as opposed to an hypothesis) is that it makes predictions

which are falsifiable.

If I assert that «Person X is a violent madman and it is only a

matter of time before he beings a Tommy gun to work and blows

everybody away," then this is merely an hypothesis, and it can never

be disproved (assuming, for the sake of argument, that Person X has

an indefinite lifespan). But if I say, «Person X will bring a Tommy

gun to work sometime during the third week of January,» then I have

turned my hypothesis into a true theory, which can then be tested.

Of course, our entire knowledge of the world is based only on

theories (beyond, that is, the famous cogito ergo sum), but this does

not mean that, within the theoretical framework of our total

worldview, theories cannot be falsified.

3.6.3) I agree.

3.6.4) "Redesigned Goals". Traditionally, Science has had the goals

of rationality, truth, objectivity and realism. But Feyerabend and

others like him, fighting against the so-called "tyranny of truth",

claim that "Equal weight should be given to competing avenues of

knowledge, such as Astrology, Acupuncture and Witchcraft" [Paul

eyerabend, quoted in Gauch 2003, p. 88].

This is simply non-sense, because no reason is offered why

«Astrology, Acupuncture, and Witchcraft,» should given equal weight.

Therefore, Feyerabend's assertions can only be met with a shrug of

the shoulders. I would argue that they are not given equal weight

because they are apparently incompatible with experimental science.

This does not mean that we are biased: they are considered on equal

ground. Just as soon as one of these «avenues of knowledge» succeeds

in proving the accuracy of a theory, due consideration will be given

to it.

3.1) Philosophy is no longer considered a Science. This seems to be

caused by an incorrect definition of "Science", and a lack of

knowledge of the "Philosophia Perennis" (or correct philosophical

tradition)

I agree that any systematic means of acquiring knowledge is,

technically, a «science.» This is practically part of the definition

of the word itself. I agree that pure philosophy should not be

denied confidence of ability to prove theories correct with the same

rigor as experimental science.

I do think that perhaps, merely for the sake of lingual convenience,

the newer connotation of the word «science" which refers exclusively

to "mechanical" or «experimental science» (natural philosophy) is not

bad. Why have two words which mean the same thing, when a useful

distinction can be made between them, and the poor writer is thereby

spared the trouble of saying «experimental philosophy» when everybody

knows perfectly well what he means if he just refers to modern

«science»?

I do not mean to disparage non-experimental science, and, as I have

said, without the benefits of non-experimental science (such as

logic), experimental philosophy would be useless to us.

4.1) Ethics is replaced by Sociology. "Good" and "evil" become a

simple consensus of such a population, in such a territory. When you

ask people infected with Religious Obscurantism to define "good" and

"evil", they'll never say: "OK, let's approach that problem

scientifically". On the contrary, they will assert with great

certainty that Science can't define good and evil, even though they

can't define Science or explain what Ethics is!

I think that a definition of «good» and «evil» can perhaps be arrived

at «scientifically.» Though, the correctness of the theory will

depend on the sensibilities of humans, I think, since what is a great

evil to a human might be a great good for a colony of fire ants

looking for a meal!

If you mean «good» and «evil» only in the sense of human thought and

action, then I think I could be fairly easily persuaded that a set of

absolute ethical principles does exist. Although, it may be

impossibly difficult to reduce this set of ethics to practice, given

the complexity of humans and the wide variety of human actions which

could be taken in different lights under different circumstances.

4.2). I agree

4.3). Neither agree nor disagree.

4.4). Ha ha!

Response to "100% of all religions are false (± 1%)"

I am absolutely fascinated by your section entitled 100% of all

religions are false (± 1%). By the way, does this include Roman

Catholicism?

In response to your section, I would argue that knowledge is

knowledge, and what you might call «imperfect knowledge» is simply a

view of the world that relies upon some correct knowledge, and some

things which one thinks are knowledge, but which are in fact pure

mistakes. The difference between our definitions is probably

semantical only.

I have said for a long time that «I believe that there is a God, but

I don't know if there is a God, and I think there is not a God.» I

separate my view of the world into what I know, what I believe, and

what I must think of as true.

First, I would argue that «ignorance» is not a type of knowledge, by

any useful definition. It is merely the absence of knowledge, and

can easily enough be called the absence of knowledge. Is the absence

of water a type of water?

3.3) Science. As you can imagine, this is the ultimate degree of

knowledge, the goal we must pursue. When we know an assertion is

true, it is because we can prove that such a thing is the way it is,

and that it cannot be otherwise. People who have scientific knowledge

say things like: "I know that the Pythagorean Theorem is true, since

this is the proof", or "Whatever you say verbally, you are

nevertheless psychologically unable to doubt that you exist as we

speak, and don't force me to put on my Philosopher's Glove to prove

it to you!" Be also careful with how words are defined. What we call

"Science" these days (like Physics, Chemistry, Biology, etc.) is

composed mostly of highly-probable opinions, strictly speaking.

I partly disagree. I assert that the ultimate degree of knowledge

about the world itself is unattainable by humans, even as to any

single aspect of it (with the one exception). This is, I feel, one

of the distinctions between man and god. I hold, like Descartes,

that all knowledge of the outside world is purely theoretical.

However it is possible to establish it with such a great degree of

certainly that the probability of error becomes mathematically

infinitesimal. These theories we can assign such a great probability

of being true that we can safely rely upon them for all purposes

absolutely. These are the things which we say we «know.» (Which you

refer to as «science,» a good term)

However, I believe that the distinction between what we know as

absolutely true about our own thoughts (Pythagorean theorem), and the

degree of certainty which we can hold about the theories applying to

the outside world is a useful one, and, I would argue, essential to

at least one avenue of proving the existence of a god.

3.4) Belief. Belief, or natural faith (as opposed to supernatural

faith), is accepting as true an assertion, but for extrinsic reasons,

not because we have evidence. In the example given above, the husband

believes there is ham in the fridge. It goes without saying that this

is a very imperfect state of our knowledge.

This is what I would call a «reasonably reliable theory.» That is,

these are theories which have a very great probability of being true,

and upon which one might rely in the conduct of serious affairs. I

disagree with your statement, «accepting as true an assertion, but

for extrinsic reasons, not because we have evidence.» On the

contrary, the husband does not have personal experience which would

conform of the veracity of his wife's assertion, but he does know

that on almost every previous occasion in his memory, an assertion

made by his wife subsequently proved to be true. This is real

evidence which supports the connection between (a) wife saying «ham

in fridge» and (b) ham existing within the fridge. This is the same

as any other induction, is it not? In addition, even personal

experience on your part could fall into this category. I am certain

that there have been times that you have looked into the fridge the

minute before, and could swear that you remember seeing eggs, only to

return and find no eggs! (OK, fine...But it happens to me!) Nobody

said that our own personal recollections are always perfectly

accurate either. I would argue that a person proving themselves to

be a reliable conduit of information is «evidence.» In fact, when a

witness (the wife) gets on the stand and testifies to the jury that

she saw a ham in the fridge on the night of the murder, her statement

is admitted into the record of the court as what? Evidence!

3.2) Opinion. Also known as "probable knowledge". A person with an

opinion has reasons to think that things are probably thus, but

without being certain. Please note that this person knows that he can

be mistaken! You can't "be sure of your opinion", because that's an

oxymoron. People who have opinions say things like: "I think the

Edmonton Oilers are going to win the Stanley Cup this year, for such

and such a reason", or "I'm 75% sure that this is so, because of such

a study, or such an argument", etc.

This is what I call «belief.» I agree that it is an assumption which

stands a good chance of being true, but which also stands a

reasonable chance of being false. I think that the useful, practical

distinction between «reasonably reliable theory» and «belief» (or

«belief» and «opinion»), is that the latter is what experimental

scientists would call a «hypothetical model.» In other words, we

acknowledge that there exists a hole in our knowledge of the world,

so in order to fill that hole, we design a hypothetical scenario

based on our best information up to that point, in order to fill the

hole with something. This «placeholder» knowledge enables us to

think about the unknown in a rational way, allows us to do risk

analysis, design intelligent experiments to prove its accuracy, etc.

The essential, practical difference between a reasonably reliable

theory and a belief (or an opinion, as you call it) is that the one

is a solid building block upon which a person is prepared to base

further knowledge, while the other is a piece of temporary

«placeholder» knowledge which enables us to think intelligently about

the world, and to make best decisions in the absence of more accurate

information, but upon which no more should be built until it is

confirmed. (In other words, in the great pyramid of knowledge, the

"belief" stones should always be on top.)

Of course, the exact point at which a theory becomes certain enough

to use as a base for further knowledge is «up for grabs» depending

upon the individual, but it at least creates a definite distinction

between a «belief» and an «opinion,» since even opinions are based on

some evidence.

By the way, you never say why you «believe» in Jesus Christ.

This is in response to "Error: The Brain In A Vat."

First, the idea which dictates that all of external reality has some

doubt about it's form is hundreds of years old, as you no doubt know,

and is in fact one of the ideas upon modern science is built! The

significance of Rene Descartes' simple statement, «Cogito ergo sum»

is that it is an absolute truth, and the one thing into which

Descartes could introduce no doubt. As I understand it,

Descartes-when modern science was first being born, and men wanted to

bring into question all that was questionable, so that we could know

once and for all what was true-proposed this as the starting point of

all knowledge. So it has remained. It also remains the single fact

about the world that we know for certain: «I exist.» Beyond this

single fact, which is known with absolute certainty, all knowledge

comes from theory of one type or another (I exclude from this

mathematics, for example, since mathematics is an idea internal to

our own minds (cogito), and does not necessarily represent true

knowledge of the outside world).

Second, our uncertainty about the absolute truth of the outside world

does not mean that there is no absolute truth about the outside

world!

I think it is clearly true that, as in the movie «Matrix», our brains

could be plugged into computers which create a virtual world for us

to live in, like a dream, leaving us blissfully unaware of the true

reality, which might be something entirely different. I do not know,

in fact, that I was born. It is hypothetically possible, at least,

that the earth was created last week, complete with relics made to

appear as though they were thousands of years old, and humans with

memories of what they think happened years ago. It is possible that

World War II didn't actually happen; that, in fact, all of human

history as it is recorded in our books and in our memories was

fabricated just last week, when the earth was created.

This is a possibility. Do I think that this possibility is any

serious threat to our scientific understanding of the world? No, of

course not. Occam's Razor (the theory with the fewest assumptions

must be assumed most likely correct) and the Null Hypothesis both

have something to say about this. And it is on these grounds that we

ignore such unsubstantiated possibilities.

Third, we don't have to disprove the possibility that our brains are

in a vat! (As you say). It is totally unnecessary. The probability

that our brains are in a vat is so infinitesimally small, that it

warrants no serious consideration.

"A Skeptic can deny these things with his words, but he can't live as

if he himself really agreed with his silly assertions!"

Of course. The idea of ignoring infinitesimally small possibilities

is not new to us. Every time you open the door to your house, there

is the theoretical possibility that there is a prowler waiting to

kill you. The actual chances? Vanishingly small. So we go about

our houses without care. Only if there is some evidence to support a

particular conclusion does it make sense to seriously entertain the

possibility (e.g., a smashed window).

Why would mere possibilities be any more of an impediment to science?

I hear that quantum theory predicts that, if you were to slap your

hand down upon the table, there is a possibility that your hand would

go straight through the table. But the chances of this occurring are

so remote that if a trillion people slapped their hands a trillion

times a second, it would not likely occur in a million trillion

years. So, does the mere existence of a hypothetical possibility

shake our confidence in the laws of physics one bit? Of course not,

because logic dictates that we build our knowledge upon theories

which are most likely to be correct.

We do not need to dispute the existence of the possibility. We

merely need to ignore it. However, as I have said, I think that the

existence of the possibility is important to at least one avenue of

proving the existence of a god.

Sincerely,

J. Ferenc

Hello J. Ferenc,

Sorry again for the very long delay in answering. As I said,

work, illness and other factors slowed me down.

>> I fear that

>> my answers may be too verbose, and that you will never read them.

I don't have a life, so I read all my e-mails very

carefully!

;-)

Seriously, I think many of my questions were not clear or misleading,

in that article called: "Isn't believing in Science anti-scientific?"

Right from the start, sorry about any confusion caused by my

poorly-worded questions, and thanks for calling those problems to

my attention.

Now, let's look at your answers in detail.

>> 2.1) Science is any systematic means of acquiring knowledge, broadly.

Concedo, if we speak broadly.

A detailed answer, in my opinion, requires a complete Philosophy

textbook (as you know, my favorite one is currently Thonnard).

>> I think its usual use in modern speech is to refer to the system of

>> acquiring knowledge using the experimental - or, more generally, the

>> "scientific"-method.

Concedo.

But one of my claims is that some variants of this modern meaning are

incorrect. I'll try to discuss this here below.

>> I would argue that there is only

>> one type of knowledge. Knowledge is knowledge, just like water is

>> water.

I think my question was not well-worded. So thanks for calling that

to my attention. I re-worded it to say:

2.2) What are the various "types of knowledge", and why is

Science better than the others?

Strictly speaking, Concedo, knowledge is

knowledge. But the word "knowledge", as far as I know, is analogous

(I'm using that word in it's technical sense here). Quick reminder

of the two types of analogy:

"analogy of attribution":

"healthy body" ("prime analog" in this case)

"healthy urine" (sign of health)

"healthy food" (one of the causes of health)

"analogy of proportion":

"Man's mind is alive because it nourishes itself

and grows by assimilating ideas, a bit like a dog is

alive because it nourishes itself and grows by assimilating

dog food."

I'm guessing some of the senses of the word "knowledge" are based

on an analogy of attribution:

"science" as "prime analog"

"opinion" as "imperfect knowledge"

"belief" as "indirect knowlege (based on our trust in someone else's

real knowledge)"

>> Knowledge which has been

>> scientifically derived is better because it is testable.

Concedo, roughly speaking. But we could argue about the

"testable" part. We know with certainty that "2+2=4", or that

"the whole is greater than any one of its part", or "I think

therefore I am", yet we don't need to repeatedly test. We just

need to think about it once.

>> Science

>> agrees that the senses are reliable

Actually, strictly speaking, the question of "Are our senses reliable"

is a philosophical question (the part of philosophy called "Criteriology",

first part of Metaphysics). So if philosophy is not a science, all our

scientific knowledge would need to be based on non-scientific knowledge!

;-)

But we need to define our terms more clearly first.

>> always tries to find ways to

>> make any knowledge testable in such a way that it-or its

>> components-can be reliably perceived by our senses

Concedo, but with a little reservation.

Do you exist mentally? Yes. Is your mental existence

perceptible with the exterior senses (eyes, nose, ears,...)?

No.

Even if you observe that certain brain waves occur

when you are conscious, you still need to be conscious

to say: "OK, measure now, I'm conscious!" Otherwise you'd

never know those brain waves are associated with anything.

Mental existence is absolutely reliably percieved, but not

by our exterior senses. This is very mysterious. True

science observes this fact.

>> to find

>> ways to prove a thing by building upon elements which can, at some

>> level, be observed and verified.

Concedo, if "verified" is not artificially restricted to "verified

by our external senses".

>> A superstitious belief [...] can and should be tested.

Concedo, in the sense that all assertions ideally should be

verified. But of course obviously silly assertions don't need

to be tested (like the example you give). I removed the

expression "superstition" from that question, which was misleading.

>> A system of knowledge which is infused with an unknown

>> amount of error, and with no reasonably reliable way of separating

>> the error from the truth, is useless.

I'm not sure I understand your statement. "A system of knowledge"

that contains no knowledge is somewhat contradictory. But once

again, I think my question was not clear.

>> 2.3) Science does not teach truth. As Indiana Jones said, "Science

>> seeks facts, not truth. If it's truth you're after, the philosophy

>> class is right down the hall."

:-D

Offhand, listening to Hollywood to get reliable information on

Criteriology, seems like listening to homeless hobos to find

out how to perform rocket science or brain surgery!

Webster's Dictionary gives "in truth" as a synonym to "in fact".

A scientist who counts the number of red blood cells on a microscope

slide is seeking for the true number of red blood cells.

If it doesn't pay attention while counting, chances are his cell

count will be false.

Redefining "truth" as "that which is not sought by scientists" is

just a Post-Modernist trick, unrelated to reality. Biologists,

Chemists, Physicists, Philosophers, etc., all pursue truth.

But you're right: my question was not well-worded. I tried to

improve the wording.

>> Truth is the absolute reality of the universe.

"Truth" is an analogous word. When you count the fingers on your

hand, if you count well, the result is "truth". "2+2=4" is a truth.

(Jesus Christ is also The Truth, but that's an advanced topic!)

>> Science does argue that since

>> humans cannot perceive truth directly

Nego.

Look in a laboratory microscope, or in a telescope, or in a chemical

formula, or in a Petri dish, and you will never see the

statement:

"Science says that men cannot perceive truth directly"

That is not an observation of experimental science. It is a

philosphical position (and a bad one at that!)

>> one truth,

>> different perceptions; one statue, different vantage points.

Well, we can argue about that one. That is a common opening

line for sceptics who try to argue that truth doesn't exist.

You'd need to give more details about your position.

>> [Have you ever read St. Augustine, "On Free Choice of the Will,"

Not the whole thing, sorry. I'm currently reading:

THONNARD, François-Joseph, A.A., Traité de vie spirituelle;

à l'école de saint Augustin

It presents an overview of St. Augustine's theology, so I'll

probably get a fairly good idea, but you'd need to indicate

what the connection is with this discussion, to help me out.

>> Short answer: The goal of the scientific method is to ensure that the

>> individual has the best possible vantage point before making the

>> observation.

Concedo, in a way. I'm not sure, because here again, you use

expressions that are sometimes used by Post-Modernists, just before

they start asserting that we can never know truth.

The goal of science is to attain truth, not a vantage point.

>> But science does not teach truth. Science

>> gives a method to more clearly perceive the truth

Well, here again we could agree or disagree depending

on what exactly you are saying.

Strictly speaking, science is the "accident" of our reason

once is has acquired truth through a demonstrative syllogism.

>> only in those

>> areas of knowledge amenable to physical observation.

Nego. See above. Restricting our capability of knowing

truth to only things percieved by our external senses is

not science, but scientism (the prejudice popularised by

Auguste Comte).

>> 2.4) Um, I don't know. With a typewriter? What do you mean?

Sorry, my bad question again. I tried to fix it.

>> the more

>> observations I have made, the more accurate my calculated "most

>> popular skirt length" will be. That is statistics in a nutshell.

Offhand, that sounds perfectly reasonable. (I need to re-read

"Doing Science; Design, Analysis and Communication of Scientific

Research", by Ivan Valiela, 2001, or some better introduction to

statistics in science.)

My concern would be more about the part of statistics used to

find correlations. Science is knowledge through "causes", and

a "cause" in experimental science is "the necessary antecedent

linked to the consequent by Nature's determinism". Sure, you

can describe the average, the standard deviation, the median,

etc., but scientists are really interested in the "why".

Statistics become interesting (and harder to use properly)

when looking for causes. For example, do public campaigns to

distribute condoms exacerbate, reduce or remain neutral to

the spread of AIDS?

>> *This is where statistics comes in really handy. How different is

>> significantly different? The mathematics of statistical analysis can

>> take two groups of data and tell us the percent probability that the

>> differences between these groups of data would arise by chance.

Sounds like what little I remember of my courses.

And "arise by chance" seems like the opposite of "the necessary

antecedent linked to the consequent by Nature's determinism".

So if you can figure out it didn't "arise by chance", then it must

have been caused.

>> 2.6) Give specifics.

Logic is divided in two: formal and material. The last part of

Material Logic is "Methodology", or how to proceed in each Science.

See: Chapter 3: The matter of Sciences or Methodology

(sorry, French only for now)

>> 2.7) A world-renowned book on "science" itself might be Discourse on

>> Method by Rene Descartes.

Hum, Descartes? He claims our external senses are untrustworthy, and

that the only source of scientific certainty

is God (and the argument he offers to prove God's existence is wrong).

If you claim that we must prove God's existence before being able

to scientifically count the number of red blood cells on a

microscope slide, then Descartes is your man!

>> Since science

>> strongly discourages reliance on authority of any kind to presume the

>> truth of statements

"Science"? How about Theology! ;-)

Here is what saint Thomas Aquinas has to say about authority (and

he just repeats what Aristotle said centuries before Christ, and

anyway it's just common sense):

«Locus ab auctoritate, quae fundatur super

ratione humana, est infirmissimus»

("Arguments from authority, when this authority is based

on human reason, are the weakest")

[Source]

>> there is no such thing as a "Science Bible."

Of course, strictly speaking. But there must be some good book out

there about science.

>> In science, reality itself is the bible, and the books on science are

>> just people's interpretation of that physical reality. The only

>> stipulation is that you must "read the bible" (that is, look to

>> physical reality for your answers).

Here again, I could agree with you. I'm a bit afraid because, as usual,

Post-Modernists often use this as a springboard to claim we can

never know reality, only subjective interpretations of it.

(By the way, the Bible itself must be interpreted. But fortunately,

God isn't a jerk, so He supplies the Magisterium to make sure

the interpretation process is correct.)

>> 2.8) [...] If you

>> want a book that is about science, but not about method, then you'll

>> simply be looking at a catalogue of all the conclusions which have

>> been reached using (or claiming to use) the scientific method.

I would roughly agree, but Science can also be studied in itself,

not just in the results it produces.

>> My own thoughts: Science looks to the observable world for its

>> answers.

You need to define "observable", as per my preceding remarks.

>> "Science," in the modern sense, is inextricably

>> connected to the physical world.

Yes, according to the prejudices of Scientism, but not in truth.

>> Any person who dares to say

>> anything about religion using science [...] is not a

>> scientist

Nego.

My next door neighbor is a Sociologist, and he studies religions.

Sociology (when well done) is scientific.

Moreover, the existence of God can be demonstrated, with

certainty. But that is opening up another debate.

>> I am given to understand that logic is a

>> form of philosophy.

... well, the first part of Philosophy.

>> logic becomes

>> verifiable and amenable to the scientific method.

Oops! Here you just lost me.

Logic becomes "verifiable and amenable"? The scientific method

comes from logic, not the other way around, right?

>> I believe that often when people try to make arguments in the name of

>> "science", they are really arguing in the name of logic (or more

>> broadly, philosophy, or more broadly, knowledge, or more broadly,

>> truth).

You "believe"?

;-)

(Strange verb to use!)

I observe that few people who use the words "science" and "philosophy"

know what they are talking about.

>> By the way, your neighbor's house is yellow with purple stripes. It's

>> the truth.

Nego. Red roof with grey stone walls.

>> P.S. - You put out a call for grammatical errors to be pointed out to

>> you.

I owe you at least 4$. Two instances of that mistake, but many more

errors in my texts. Note that the price I pay has no correlation with

the gravity of the mistake, hence the very low pay for all the

hard work you supplied!

>> By the way, in my other e-mail I state that science argues that

>> humans cannot directly perceive truth (absolute reality). I then

>> carelessly proceed to speak of "perceiving the truth"! Whenever I

>> speak of perceiving truth, what I mean is "to perceive things with

>> our senses, or with our minds, which enable us to form a mental image

>> of the truth."

Hum, that sounds like rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic.

When you stick your hand in front of your face, count your fingers,

and declare: "My hand has five fingers", you're percieving a chunk

of physical reality, and describing it accurately. You're telling

the truth. Period. It's the truth. Absolute, certain truth.

>> Best of luck with your work!

"Luck"?

It's God's grace and hard work!

;-)

>> In Section 3.6 of «Public Enemy #1: Religious Obscurantism»

OK, Step 2 of our conversation...

>> It has been said, «You can prove something a thousand times, but you

>> only have to disprove it once.»

This is playing on words, as usual. If it is proven, it's proven. The

reason some assertions are disproven is because they were never proven

to begin with.

In order to figure this out, we need to better define what is a "theory"

in experimental science, and what is a "proof" (strictly speaking, and

then other, looser meanings).

>> As an example: I propose the theory that heavier objects will fall

>> faster than lighter objects.

I think it should be "hypothesis", not "theory", but I understand

your example.

>> It will not be

>> until one of us, perhaps by chance, takes the paper and crumples it

>> into a ball before dropping it that we will realize that something is

>> wrong with the theory.

Well, strictly speaking, something was wrong with the experiment design.

"It turns out that ensuring that the treatment and control differ in

just one aspect that tests the question ... is considerably more

demanding". (p. 79, Valiela 2001)

>> That's the

>> thing about theories: you can prove them correct as many times as you

>> like

Once again, the word "prove" is incorrectly used. What the repeated

experiments did was establish an opinion (probable knowledge). But

by definition, when you have an opinion, you know you could be wrong.

Most of "science" (modern sense of the word) is not "science" (thomist

sense of the word), but opinion (i.e. probable knowledge).

>> but that does not mean that one day an observation will not be

>> made which will necessitate a modification of theory which had worked

>> so well up to that point.

For example, the Law of conservation of Mass. I've heard, in the

experiment described in Section 2 of "Papal Infallibility, and the Stupid Gods",

that now we can measure the amount of mass lost through the emission of

light from the candle. So the Law of conservation of Mass is "wrong"!

But a good scientist would have only concluded "that when you weigh the

whole thing after the candle has burnt down, you will apparently have

the same mass." So he won't be impressed with the Post-Modernist

sleigh of hand claiming that "what used to be a scientific truth has

now been falsified"! On the contrary, it apparently had

the same mass, and still apparently has the same mass after the candle

has burnt! What was true is still true, but his opinion has been

refined.

>> I assert

>> that all observations are true, inasmuch as they are accurate.

Concedo.

>> But

>> which observations we choose to make, and our evaluation of the

>> importance of these observations, can be influenced by our

>> preexisting theory, or our lack of a theory.

Concedo.

>> then I have

>> turned my hypothesis into a true theory, which can then be tested.

For some reason, I think you've flipped "theory" and "hypothesis".

But I agree with your explanation, of course.

>> our entire knowledge of the world is based only on

>> theories

Nego, but then because of your incorrect definition of

"science", that is understandable.

>> This is simply non-sense, because no reason is offered why

>> «Astrology, Acupuncture, and Witchcraft,» should given equal weight.

Well, I'm glad I got that reaction out of you here!

>> pure philosophy should not be

>> denied confidence of ability to prove theories correct with the same

>> rigor as experimental science.

"same rigor"?

Far more rigor! (for some parts of philosophy)

>> to "mechanical" or «experimental science» (natural philosophy)

Philosophy of Nature is not the same thing as experimental science.

>> Why have two words which mean the same thing, when a useful

>> distinction can be made between them, and the poor writer is thereby

>> spared the trouble of saying «experimental philosophy» when everybody

>> knows perfectly well what he means if he just refers to modern

>> «science»?

Because if philosophy isn't a science, neither is modern experimental

science. See my comments above for Criteriology.

>> I do not mean to disparage non-experimental science

That is a contradiction in terms. "Experimental" in the sense of

"being in contact with reality" is absolutely necessary for

science, any science.

>> If you mean «good» and «evil» only in the sense of human thought and

>> action, then I think I could be fairly easily persuaded that a set of

>> absolute ethical principles does exist. Although, it may be

>> impossibly difficult to reduce this set of ethics to practice, given

>> the complexity of humans and the wide variety of human actions which

>> could be taken in different lights under different circumstances.

Hum, here again, you seem to be infected with Post-Modernism and a

lack of knowledge of "What is Morality". But we'd need to have many

hot chocolates and long discussions together.

>> Response to "100% of all religions are false (± 1%)"

>> By the way, does this include Roman

>> Catholicism?

Yes, in the 1 percent.

>> The difference between our definitions is probably

>> semantical only.

I think so (it's my opinion!)

>> I think there is not a God.»

Why?

>> First, I would argue that «ignorance» is not a type of knowledge, by

>> any useful definition.

Concedo. I modified my text.

>> I assert that the ultimate degree of knowledge

>> about the world itself is unattainable by humans

Well, how could you make such an ultimate assertion? We cannot

know absolute truth about the world itself, and you're making

an assertion about the world itself (i.e., that we can't know

it fully).

>> I hold, like Descartes,

>> that all knowledge of the outside world is purely theoretical.

Well, I don't think Descartes would have agreed with you (and

I certainly don't!)

:-)

>> However it is possible to establish it with such a great degree of

>> certainly that the probability of error becomes mathematically

>> infinitesimal.

If you're standing in the middle of a highway, and there is a car

coming toward you, you will be crushed if you stay there and

the car hits you. There is no uncertainty there. That's not a theory.

>> This is what I would call a «reasonably reliable theory.»

Hum. You're losing me here.

>> the husband does not have personal experience which would

>> conform of the veracity of his wife's assertion, but he does know

>> that on almost every previous occasion in his memory, an assertion

>> made by his wife subsequently proved to be true.

That's exactly what I'm saying. The husband has evidence about

the intelligence and good will of his wife, but no evidence

whatsoever about what is in the fridge.

>> This is the same

>> as any other induction, is it not?

No, not at all.

>> and could swear that you remember seeing eggs, only to

>> return and find no eggs!

Concedo, but for dollar bills in my wallet!

;-)

>> her statement

>> is admitted into the record of the court as what? Evidence!

Precisely! The word "evidence" in that context is a perfect example

of "verbal inflation". See #2.2 in:

Verbal Inflation and Impoverished Thought

>> This is what I call «belief.»

Incorrectly.

>> a reasonably reliable

>> theory and a belief (or an opinion, as you call it)

The word "opinion" was invented and used for millenia before

you and I appeared. I'm not inventing that word or its

correct meaning.

>> By the way, you never say why you «believe» in Jesus Christ.

Not in that article (it's in the "Philosophy" section of my web

site, so I try to steer away from religion, and keep that for

the "Lost Sermons" section).

Reasons to believe are given in the part of Theology called

"Apologetics". There are many good books on the topic, some

are listed in my "Some Good Books" section.

>> This is in response to "Error: The Brain In A Vat."

>> [...] and is in fact one of the ideas upon modern science is built!

Nego.

>> So it has remained.

Nego.

>> It also remains the single fact

>> about the world that we know for certain: «I exist.»

Nego.

>> I think it is clearly true that, as in the movie «Matrix», our brains

>> could be plugged into computers [...] when the earth was created. [...]

>> This is a possibility.

Not really, but then I don't smoke pot.

;-)

>> And it is on these grounds [Occam's Razor, etc.] that we

>> ignore such unsubstantiated possibilities.

Concedo, we ignore them, but Nego, about "on these grounds".

>> So we go about

>> our houses without care. Only if there is some evidence to support a

>> particular conclusion does it make sense to seriously entertain the

>> possibility (e.g., a smashed window).

Concedo.

>> I hear that quantum theory predicts that, if you were to slap your

>> hand down upon the table, there is a possibility that your hand would

>> go straight through the table.

Never saw that in the only book I have discussing quantum stuff

(ATKINS, Peter. Physical Chemistry, 6th Ed., 1997.).

But then I don't understand quantum stuff very much.

>> I think that the

>> existence of the possibility is important to at least one avenue of

>> proving the existence of a god.

I'm not sure if I understand you, here.

Cheers!

Stefan